by Sean Braswell (12-10-20)

Talk about hidden figures. We’ve put together some of the untold stories behind some of the most remarkable, inspiring and ruthless individuals in history, from badass women to unsung Black pioneers to long-forgotten monsters. This is what they didn’t teach you in school. Class is now in session.

unsung black pioneers

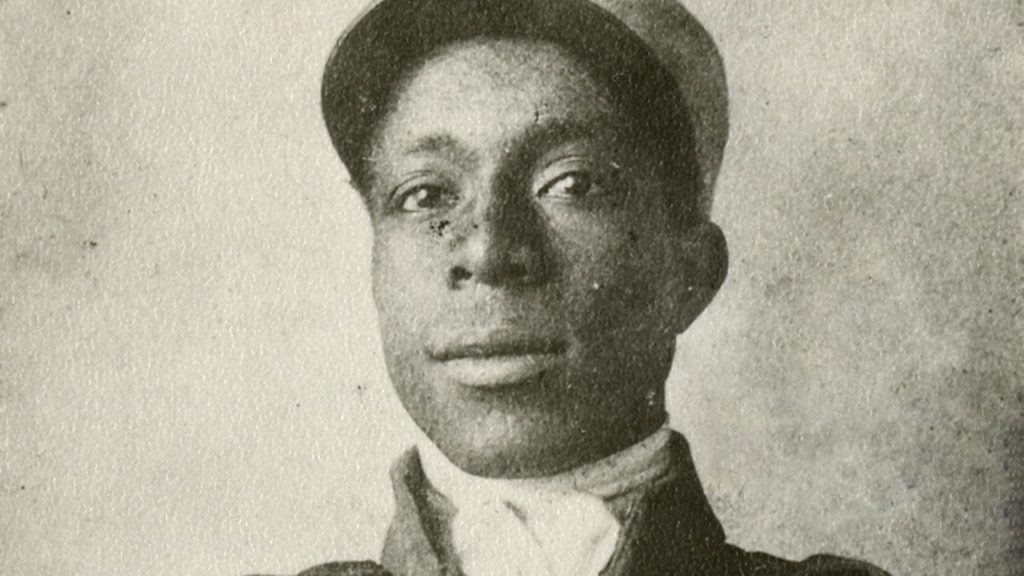

1. Isaac Burns Murphy

by By Nick Fouriezos

This champion Black jockey read thoroughbreds like Hank Aaron read pitchers and dominated Churchill Downs like Tiger Woods dominated Augusta National. According to one tally, Murphy, who was born into slavery, won 530 of 1,538 races, a 34 percent rate that still dwarfs the greatest all-time official tallies in horse-racing record books. He would win his last Kentucky Derby in 1891 — before retiring as the first person ever to win it three times.

Isaac Burns Murphy cased the track like Muhammad Ali did the ring, read thoroughbreds like Hank Aaron read pitchers and dominated Churchill Downs like Tiger Woods dominated Augusta National. Which is to say that, when it comes to the sport of horse racing, he was the most idolized and scrutinized athlete of his time, worshipped by Black and white fans alike.

Yet Murphy is obscured, whitewashed by a sport that wasn’t ready for his celebrity or his blackness. That’s because, unlike his peers in the athletic pantheon, Murphy was born into slavery, in January 1861, two months before the inauguration of President Abraham Lincoln. And with the 145th running of the Kentucky Derby taking place this Saturday, it’s worth reflecting on the larger-than-life story of Murphy and the other Black jockeys who dominated the nation’s most popular sport of the late 19th-century — before the rise of Jim Crow laws and racist tactics within the sport lashed back.

AT THE HEIGHT OF HIS FAME, HE WAS MAKING TENS OF THOUSANDS OF DOLLARS A YEAR FROM WEALTHY BREEDERS, MAKING HIM THE HIGHEST-PAID JOCKEY IN THE U.S.

Murphy’s success began with an unintended consequence of slavery: It was an environment that threw Black men into working with horses from an early age. As Emory University professor Pellom McDaniels III wrote in his biography of Burns, The Prince of Jockeys, the future star grew up in a postwar Kentucky where the development of prized sheep, cattle and, yes, horses were left to the formerly enslaved — it was work seen as beneath the stature of the white elite. “As horse racing became exceedingly important to the landed gentry, grooms, trainers and jockeys rose in prestige on Kentucky farms,” McDaniels writes.

That created an opportunity for Black men to rise to prominence in the sport. Raised alongside Black horse-racing peers such as Pike Barnes, Soup Perkins and Willie Simms, Murphy began racing at the age of 14, with his first win in September of 1875. That was also the year of the first Kentucky Derby, where 13 of the 15 jockeys (including winner Oliver Lewis) were Black men. Two years later, Murphy would ride in the Derby for the first time, placing fourth.

Most jockeys dug into their mounts with a whip and a crouched, bullying stance, but the teen Murphy rode crouched and urged his charge forward with calming words. As others galloped ahead, he conserved his horse’s stamina, only to press forward at the end of races to snatch victory over his competitors’ worn steeds.

The unconventional tactics led to victory. He would win the Kentucky Derby for the first time in 1884, and the Kentucky Oaks and the Clark Handicap that same year — a trifecta he’s still the sole jockey to accomplish. According to his own analysis, Murphy won 628 of his 1,412 starts, an absurd 44 percent victory rate (another calculation, conducted later, had him at 530 of 1,538, a 34 percent rate that still dwarfs the greatest all-time official tallies in horse-racing record books). He became known as “The Colored Archer,” a reference to the English racing great Fred Archer, although, ironically, it was Archer who was taking after Murphy. “Archer picked a lot of his mannerisms in the saddle and spread them throughout England,” says Brien Bouyea, communications director for the National Museum of Racing and Hall of Fame.

To say Murphy became a victim of his own success would be to mistakenly erase the culpability of those who were truly responsible for his downfall. At the height of his fame, he was making tens of thousands of dollars a year from wealthy breeders, making him the highest-paid jockey in the U.S. “Murphy was the first millionaire Black athlete,” as Joe Drape, author of Black Maestro, told CNN in 2013.

But Murphy’s ascension was troubling the status quo. The idea that their young sons were idolizing a Black man likely troubled many of the sport’s wealthy white patrons, says Katherine Mooney, a history professor at Florida State University. “That is a whole different mindfuck for somebody who is fundamentally racist,” she says. After a famous victory at Sheepshead Bay in 1890, Murphy gave an interview to the Black journalist T. Thomas Fortune. While his words were simple — “I ride to win,” he said — Fortune wrote that it was men like Murphy who would lead the fight to end U.S. racism. That same year, he won the Kentucky Derby again.

Soon after, Murphy fell off his horse after a race. Critics pounced, saying he was drunk on the job, which Murphy vehemently denied. It’s still a matter of dispute. Alcoholism and extreme crash-dieting tactics — including eating tapeworms — were the scourge of the racing world as jockeys struggled to drop pounds.

His reputation didn’t recover in his lifetime. He would win one more Kentucky Derby in 1891 — riding the first, and only, winning horse owned by a Black man (Dudley Allen) — before retiring as the first person to ever win it three times. He died of heart failure, in February 1896, at age 35. Three months later, the Supreme Court upheld Plessy v. Ferguson, which confirmed the constitutionality of a Jim Crow law in Louisiana, paving the way for segregation efforts across the South.

African American jockeys had won the Derby in half the races from 1875 to 1905, and Murphy was entered into the Racing Hall of Fame upon its inauguration in 1955 (an annual award is even named after him). But no African American jockeys rode in the Kentucky Derby at all from 1921 to 2000. In this year’s race, there are jockeys from Venezuela, Colombia, France and Jamaica, but no African American riders. As Mooney writes: “The history of the Kentucky Derby, then, is also the history of men who were at the forefront of Black life in the decades after emancipation — only to pay a terrible price for it.”

2. Eugene Bullard

by Jack Doyle (1-22-2016)

“THE TRUTH IS OUR FIGHT, AND THE FIGHT OF THOSE WHO LOOKED UP TO US AS HEROES, DIDN’T END WITH THE ‘WAR TO END ALL WARS.’ ”

Born in rural Georgia to a large, poor Black family, Bullard stowed away on a ship bound for the U.K. in 1912 and ended up in Liverpool, where he launched his career as a formidable boxer. He later moved to France, joined the French Foreign Legion and became the first Black fighter pilot. If that wasn’t enough, Bullard managed one of the most fashionable jazz clubs in Paris after World War I and served as a spy for the French Resistance during World War II.

You never know who you’re sharing an elevator with — and back when Rockefeller Center still had elevator operators, it was easy to ignore the elderly Black man in the corner. Neither Eugene Bullard nor his neat uniform commanded the same attention as the 1950s Manhattan elites who shared his little space every evening.

But little did they know that they were sharing a lift with an American who had been smack in the middle of the most dramatic twists and turns of the 20th century. Bullard was a boxer, World War I fighter pilot, Paris nightclub owner and World War II resistance fighter. He escaped the Gestapo and was beaten by police at a civil-rights demonstration. But even for many years after his death, his legacy remained that of an unnoticed, forgotten elevator operator.

Many details of Bullard’s life remain shrouded in myth, some of which was his own making. And who can blame him? He was born in rural Georgia to a large, poor Black family, and the odds were stacked against young Eugene. His family struggled to support themselves and, by Bullard’s recollection, faced violence with terrifying frequency. A lynch mob killed his older brother, Hector, and Eugene nearly lost his life on more than one occasion to racist attacks.

But when Bullard was a teenager, he found an unlikely escape — he stowed away on a ship bound for the U.K. in 1912 and ended up in Liverpool, where he launched his career as a formidable boxer. He soon took his show on the road and became one of thousands of Black Americans seeking fortune in France. France in the early 1900s wasn’t exactly an antiracist utopia, but it was a huge improvement on Georgia. He wrote later in life that “the French democracy influenced the minds of both white and black Americans there,” helping them to “act like brothers” and convincing him that “God really did create all men equal, and it was easy to live that way.”

When war broke out in August 1914, he joined the French Foreign Legion and, after several months in the trenches, he applied to become a fighter pilot. To the surprise of many white Americans who were already flying, Bullard was accepted, becoming one of only two recorded Black flyboys in the entire war. Photos from Bullard’s time as a “knight of the air” show a rakish young fighter pilot. He had a pet monkey named Jimmy and painted a defiant slogan on the side of his plane: “Tout le Sang Qui Coule Est Rouge” — or “All Blood Runs Red.” Though he had no official kills, he quickly gained respect as a capable, professional pilot. He also got into a few fights on the ground, mostly with white soldiers who had a problem with his race — and, as a professional boxer, he usually made his point clear.

But even though Bullard had been a brave, reliable flyer for France, the U.S. Army ignored his transfer application. He took this to heart, remaining in his adopted land after the war and managing one of the most fashionable jazz clubs in Paris, Le Grand Duc. His guests included fellow African-American ex-pat Josephine Baker, the Prince of Wales, F. Scott Fitzgerald and Ernest Hemingway. For a while, he even had his own club, calling it L’Escadrille.

After the Nazis invaded France in 1940, his clientele started to include top German officers. Bullard, who spoke German, offered to spy for the French Resistance — and was even wounded fighting again for the French cause. With Europe heating up, Bullard and his French-American children made a hasty but necessary move back to the United States that left the family with little money and far fewer options than in France. After settling in a tiny apartment in Harlem packed with World War I model airplanes, Bullard took up his least glamorous job yet, as a Rockefeller Center’s elevator operator, where he remained — largely anonymous — for the rest of his life.

“He had many reasons to resent his native country,” says biographer Craig Lloyd. But Bullard never “gave up his American idealism.”

A hundred years later, the contributions of Black soldiers have gone largely ignored. Bullard’s name is still missing from the French memorial commemorating American World War I flyers. Recently, Max Brooks’ graphic novel The Harlem Hellfighters brought the story of the legendary African-American regiment back to life — but hammered home a grim truth through the novel’s narrator that reminds us of Bullard’s story.

“The truth is our fight, and the fight of those who looked up to us as heroes, didn’t end with the ‘War to End All Wars.’ ”

3. Rebecca Lee Crumpler

by Sean Braswell (2-25-19)

The first Black woman in America to earn a medical degree, Dr. Crumpler served as a nurse for the Freedmen’s Bureau during the Civil War, where she helped minister to the medical needs of as many freed slaves as she could. That experience gave her the opportunity to treat an unprecedented number of patients, and like Florence Nightingale, who wrote at length about medicine following her wartime service, Crumpler composed a medical treatise that was not only historic but also invariably useful.

It’s somewhat hard today to appreciate just what an accomplishment the 145-page treatise A Book of Medical Discourses in Two Parts represents. Even the title of the 1883 work is misleadingly modest. One of the first American medical guides to offer advice for women and children, the book deals with treating everything from infant bowel complaints to hemorrhoids and diphtheria. It even offers marital advice: one way to stay happily married “is to continue in the careful routine of the courting days, till it becomes well understood between the two.”

Dedicated “to mothers, nurses, and all who may desire to mitigate the afflictions of the human race,” Medical Discourses is the masterwork of Dr. Rebecca Lee Crumpler, the first Black woman in America to earn a medical degree. She managed to blaze a path through the medical profession at a time when few Blacks or women were able to attend medical school, let alone publish books about their work.

Few photographs survive of Dr. Crumpler, and what we know about her comes mostly from her own writings. Born in 1831, she says she was raised by a “kind aunt in Pennsylvania” who spent much of her time caring for sick neighbors so that the young Rebecca “early conceived a liking for, and sought every opportunity to relieve the sufferings of others.” At the age of 21, Crumpler moved to Charlestown, Massachusetts, where she worked as a nurse for eight years and set her sights on the New England Female Medical College.

Based in Boston and attached to the New England Hospital for Women and Children, the medical school accepted its first class of 12 women in 1850 at a time when many male physicians still argued that women were too sensitive or did not have the physical strength or intellect to handle the rigors of practicing medicine. In 1860, Crumpler applied to the New England Female Medical College and was accepted. Four years later, she received, as she put it, her “degree of doctress of medicine,” becoming the school’s first and only Black graduate (it closed in 1873). Crumpler’s accomplishment is even more impressive when you consider the broader context: Of the 54,543 physicians in the United States in 1860, only 300 were women, and none of them were Black. But Crumpler’s graduation also coincided with a remarkable period of upheaval in American history, one that put an incredible strain on America’s medical profession: the Civil War and its aftermath.

The Civil War, says James Downs, a professor of history at Connecticut College, “was the largest biological catastrophe of the 19th century. More soldiers died from disease than from battle or even battlefield wounds.” According to the Library of Congress, an astonishing 29,000 of the 100,000 Black soldiers serving in the Civil War died from disease, about nine times the number that would perish fighting. And even after the war ended, as Downs chronicles in Sick from Freedom: African-American Illness and Suffering During the Civil War and Reconstruction, conditions were not much better in the Black community, especially for freed slaves.

Emancipation and the long war left millions of African-Americans without adequate shelter, food or access to medical care. In the fall of 1865, there were only about 80 doctors and a dozen hospitals available to treat more than 4 million freed slaves. And most of the hospitals run by the Freedmen’s Bureau, the federal agency charged with helping those freed slaves, could treat no more than 20 patients at a time because of lack of funding.

It was an almost unimaginable public health crisis, and in 1865, Dr. Crumpler — one of the few Black women employed by Freedmen’s Bureau — rushed headlong into the breach, leaving Boston for Richmond to minister to the medical needs of as many of the freed slaves as she could. In addition to her desire to help a population of more than 30,000 people, she knew her extensive field experience in Virginia would provide her “ample opportunities to become acquainted with the diseases of women and children.” According to Downs, the Civil War offered physicians like Crumpler “the opportunity to treat an unprecedented number of patients and to learn more about medicine and the body.”

In 1869, Crumpler returned to Boston where she treated poor women and children from her home before turning her attention to her treatise, a work based on the voluminous journal notes she had kept during her years of practice. The covered topics included everything from breastfeeding and dietary guidelines to the treatment of measles, burns and cholera. “What makes Crumpler’s work particularly powerful,” says Downs, was not just how it grew out of her own experiences, but how “she frames her book as a more general study on womanhood and does not follow the traditional practice of segregating Black women and their children’s health as separate from White women’s health.”

Like Florence Nightingale, who wrote at length about sanitation and medicine following her wartime service in the Crimean War, Crumpler composed a work that was not only historic but also invaluably useful. And her legacy continues to inspire. “Her mere presence in the annals of history challenges how many imagine the past,” says Downs. “It undermines a racial ideology that persists today by presenting Black achievement in medicine as surprising and new.”

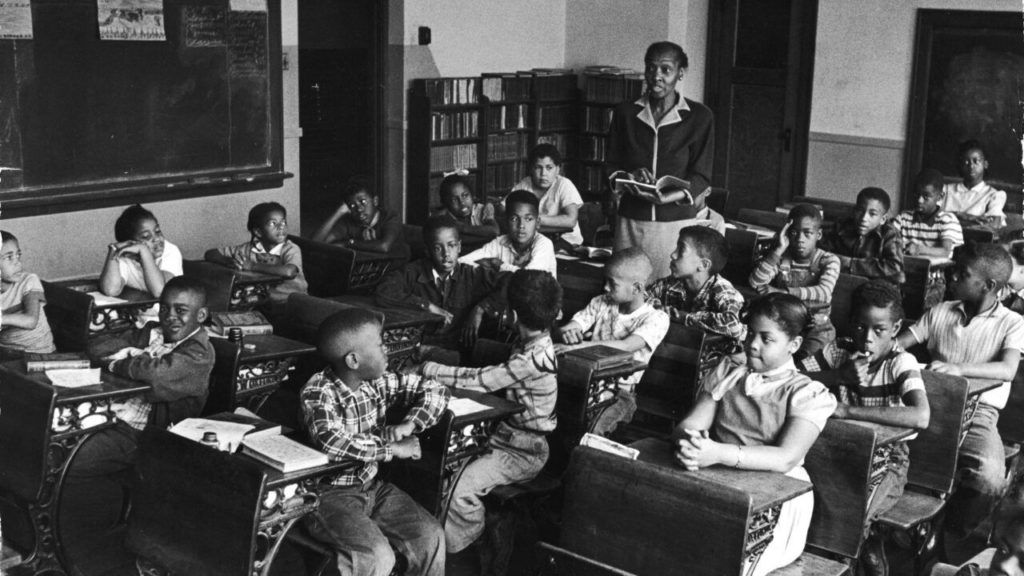

4. The Forgotten Century

by Christina Greer (12-9-20)

For many Americans, the racial justice progress and setbacks from the end of the Civil War to the civil rights era of the 1960s are little studied or understood. But what occurred during the 100 years in between has had lasting effects on Black American advancement and race relations (or lack thereof). Our policy debates today on housing, education, public health, segregation and much more can be traced directly to this period. It’s high time for more education about the white backlash to Reconstruction, and the campaigns of terror against Blacks, argues professor Christina Greer.

When discussing the history and contributions of African Americans in the United States, far too often there is a vague understanding of their legacy of in this country. Part of the failing comes from the U.S. education system, which has consistently provided a vague analysis of roughly 300 hundred years of chattel enslavement of Africans on American soil. In addition to a history that consists of “slaves” and “slaveholders,” the education system glosses over a full century of American struggle and progress that followed the end of the Civil War.

For many Americans, their understanding of the era following the end of the Civil War in 1865 often jumps from President Abraham Lincoln “freeing the slaves” and his relationship with African American abolitionist Frederick Douglass, to 1960s president Lyndon B. Johnson and his relationship with civil rights leader Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. with the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. But what occurred in the 100 years in between has had lasting effects on Black American advancement, race relations (or lack thereof), issues pertaining to housing, education, public health, segregation and, realistically, almost every policy issue we continue to discuss today.

The process of Reconstruction began at the conclusion of the Civil War. During this period, African Americans were elected to statehouses in the South, historically Black colleges and universities and African American organizations were founded, and Blacks began moving to states throughout the newly reunified nation. The Reconstruction period exhibited great progress for Black Americans and was met with a harsh backlash by white Americans for decades to follow.

In response to African American advancement, whereby Blacks founded towns, banks, schools, churches, small businesses, organizations and newspapers, whites notoriously burned down these institutions to intimidate and terrorize communities and exert white supremacist ideals. Oftentimes, Black Americans could not rely on local police departments for protection or even white clergy members, as many were part of the vigilante groups perpetuating the violence after-hours with groups like the Ku Klux Klan.

During this time, countless brave African Americans attempted to change their fate and become active participants of the electoral process. The 15th Amendment in 1865 granted Black men the right to vote, and the 19th Amendment in 1920 granted the same to (white) women. However, what was legally on the books was often not followed in practice, especially in the South. At the turn of the 20th century, African American freedoms and integration were rolled back and Jim Crow laws were implemented, making it illegal for Black Americans to attend certain schools, ride public transportation, use public facilities or integrate fully into American life. One of the ways to maintain these segregationist laws was to prevent African Americans from voting by implementing rules like literacy tests, poll taxes and grandfather clauses. These policies required African Americans to take tests with impossible questions (e.g., How many bubbles are in a bar of soap?), pay an extraordinary fee to be able to register to vote or prove that their grandfather had voted, a rule most descendants of enslaved people could not satisfy.

For those who were persistent during this period, whites often used lynching and rape as a tool to control and intimidate Black men and women. Lynchings were often a community affair in which women and children were brought to the public sphere to witness the lynching of a Black man. Souvenirs from the deceased were often collected and sold, pictures were taken, and postcards were made so whites could send them to their friends and family in other parts of the country. Lynchings were often carried out against leaders in the community who attempted to organize others to vote or participate in civil rights. Recent research has shown that economic and business leaders were often targeted in order to decrease the economic viability and strength of Black communities. At other times, random people were lynched for no reason at all.

Those who tried to register to vote or mobilize others to do so often faced economic repercussions, such as losing a job or being blackballed from economic opportunities in the community. All of these negative responses and obstacles for Blacks attempting to exercise their constitutional rights worked against African American integration into the electoral space. It was not until 1965, with the passage of the Voting Rights Act, that African Americans were granted the full franchise. (For a little context, I was born just 13 years after the passage of this act.)

There were countless Black Americans during this period who marched, protested, wrote, dared to vote, published newspapers under threat of violence, preached sermons to educate and dared to integrate spaces and schools under the threat of severe violence or worse. The years between 1865 through 1965 were filled with horrific violence toward Black Americans, who, while no longer bound to chattel slavery, were definitely not integrated fully into American society. Thousands of African Americans served their country and fought in wars to liberate others while not being fully liberated themselves at home. Sadly, some were even lynched in their military uniforms upon returning home, while others were denied GI Bill benefits and the opportunities afforded to white veterans to purchase a home or attend a university.

It is imperative we take full stock of what has happened in this country before we can begin to move forward as a nation united. The 100 years of forgotten American history in textbooks erases so many American heroes who loved and fought and died for a nation that did not return a modicum of acknowledgment or acceptance. Every American should know this aspect of the nation’s history, because Black history is American history. There isn’t one without the other.

5. James Forten

by Sean Braswell (10-16-18)

THIS BLACK ACTIVIST WAS ONE OF THE RICHEST MEN IN EARLY AMERICA.

FORTEN ENLISTED TO FIGHT FOR A PROSPECTIVE COUNTRY THAT DID NOT EVEN CONSIDER HIM ONE OF ITS CITIZENS.

The Thread, OZY’s hit weekly podcast. In Season 3, The Thread charts how a revolutionary idea — nonviolent resistance — changed the course of history.

When the American colonies went to war with the British, the 14-year-old Forten enlisted to fight for a prospective country that did not even consider him one of its citizens. After several years of fighting, including a stint as a prisoner of war aboard a British vessel, Forten returned to Philadelphia, where he would become one of the most successful Black businessmen in the new nation, pumping his time and his money into the twin causes of abolitionism and civil rights.

In the spring of 1842, several thousand Philadelphians poured into the streets for one of the largest funerals in the city’s history. It was a remarkable sight: An interracial procession that included everyone from poor Black laborers to wealthy White merchants to sea captains and shippers. On that March day in Philadelphia, one observer wrote, “complexional distinctions and prejudices seemed … forgotten.” One visitor from Great Britain, who happened to be in the city that day, was awestruck by the integrated funeral. He inquired of the deceased, “Who was this man?”

That man, James Forten, had lived a life in early America that was hard for many in his time, or even for us in retrospect, to imagine. In an era in which Black people in America were oppressed and many enslaved, Forten managed to beat the odds to become a rich sailmaker and amass a large personal fortune. But Forten’s story is not just one of a Black man who rose to be one of the wealthiest in Philadelphia, but of a devoted patriot who believed in making the ideals of his country a reality for all of its citizens — and, as we cover in this week’s episode of OZY’s hit podcast, The Thread, one who used his great wealth and privilege to help fuel a movement that would alter the course of his country’s future.

Forten was born in Philadelphia in 1766 in modest circumstances, but legally free. It was a time of turbulence and revolution, and the young man witnessed a British occupation of his city and the buildup to war. The 10-year-old Forten even stood in the crowd on a hot day in July 1776 and heard the Declaration of Independence read to the public for the first time — an experience that remained with him his entire life.

And when the American colonies went to war with the British, Forten enlisted to fight for a prospective country that, despite its “all men are created equal” rhetoric, did not even consider him one of its citizens. “He really does have to decide as a person of African-American descent where his loyalties are, and it would have been easy to say, ‘Just wake me up when the revolution is over,’” says Julie Winch, author of A Gentleman of Color: The Life of James Forten. But Forten joined the patriot cause, she explains, “convinced it will eventually bring about a fairer and more just society.”

Forten was just 14 years old when he signed up for the war effort as a sailor. After several years of fighting, including a stint as a prisoner of war aboard a British vessel, Forten returned to Philadelphia — where he would become one of the most successful Black businessmen in the new nation. Starting as an apprentice to a White sailmaker named Robert Bridges, Forten gradually won his mentor’s trust, which in turn helped him win the trust of the sea captains and ship owners who would turn to the young Black sailmaker for their sails once Bridges retired. Forten built a thriving business over the years, one with an interracial workforce and the goal of helping Black common laborers make the leap to skilled artisans the way he himself had once done.

But Forten didn’t stop there. “He could have simply taken the money and forgotten the fate of the majority of Black people in his hometown,” says Winch, “but that was not the belief system he subscribed to.” Forten pumped both his time and his money into the twin causes of abolitionism and civil rights, and his pursuit of these goals quickly made him into a leading spokesman in the Black community — and a major donor to those seeking to advance related causes.

And so, when a 25-year-old editor and fervent abolitionist named William Lloyd Garrison approached Forten for help in starting an anti-slavery newspaper called The Liberator in 1830, Forten didn’t hesitate to back the effort. Forten and Garrison became close friends, and Forten, then in his 60s, helped provide the editor with not only money but also introductions to Philadelphia’s Black leaders and a steady stream of inside information. Forten even penned his own column for The Liberator, which would become the most important anti-slavery publication in America, under the pen name “A Colored Philadelphian.”

When Forten died a decade later, praise and condolences came in from all across the country and the world. From Boston, it was Garrison who perhaps summed up his friend, patron and mentor best: “He was a man of rare qualities, and worthy to be held in veneration to the end of time.”

Little-Known Revolutions

1. The Battle of Blair Mountain

by Jack Doyle (1-8-17)

THE SIGNIFICANCE OF CLASS CONFLICT IN THE MAKING OF AMERICA IS OVERLOOKED AND MISUNDERSTOOD.

For a week in the late summer of 1921, planes buzzed, machine guns rattled, gas hissed and bombs whistled through the air around Blair Mountain, West Virginia. The Battle of Blair Mountain was the biggest fight in a conflict known as the Coal Wars. After a five-day standoff between private security forces and impoverished coal miners trying to unionize, President Warren G. Harding declared martial law in West Virginia and sent in the U.S. Army to put an end to the coal miners’ resistance.

Over the past few years, we’ve become familiar with the weapons of American police brutality, from tear gas and rubber bullets to automatic weapons. But few realize just how long these tactics have been in play. Nearly 100 years ago, the U.S. federal government was dropping bombs on civilians in rural West Virginia.

For a week in the late summer of 1921, planes buzzed, machine guns rattled, gas hissed and bombs whistled through the air around Blair Mountain. It was like a scene out of World War I — a war that had ended just a few years earlier. Now, the United States was fighting itself in a conflict known as the Coal Wars, and the Battle of Blair Mountain would be the biggest fight yet. Impoverished coal miners risked everything to try to unionize and establish some basic rights for themselves and their communities.

Outside West Virginia, the Battle of Blair Mountain is little remembered, but it shaped the politics of the region in surprising ways. Our “dominant middle-class ethos,” historian Robert Shogan says, is part of why we shy away from historical memories like Blair Mountain. “The significance of class conflict in the making of America is overlooked and misunderstood,” he explains. But with coal country currently undergoing a dramatic 21st-century political awakening, Blair Mountain is a testament to the power of American labor — and a lasting insight into the region’s political strife.

The turn of the century saw coal become one of the world’s most precious commodities. That refocused whole regions of the U.S., especially Appalachia, around mining — and put increasing pressure on miners to work long, punishing hours in harsh conditions. The intention may have been to make America great again, but the push for superpower status after World War I came at a tremendous cost to miners themselves. If they weren’t killed in a cave-in or starved on poor wages, injuries and lifelong health problems abounded. And coal companies policed mining communities with private security, making sure that anyone caught speaking out against conditions was swiftly — and violently — silenced.

The miners who worked around Blair Mountain knew a little about how to better their situation; some waged work stoppages and strikes to get results. But miners elsewhere had unions — now considered a mixed bag by the American workforce, but at the time a cutting-edge way to establish unprecedented rights. Blair Mountain’s miners came from several different counties in West Virginia and knew that together they had significant clout that could sway the bosses, or even the state and federal governments. To unionize, though, they were going to have to take matters into their own hands — and that meant trading tools for guns.

One confrontation exploded the situation between miners and the Stone Mountain Coal Company: the killing of a well-known pro-miner sheriff, Sid Hatfield, by private security hired by the coal company. Thousands of miners from several West Virginia counties banded together with one intention: to unionize the miners of Logan and Mingo counties.

That led to a battle that shocked the nation. With upward of 10,000 miners ready to fight for their rights, it became clear that 3,000 police and local volunteers wouldn’t be enough to hold off the tide. Planes dropped bombs on the miners at the direction of military aviation pioneer Billy Mitchell. Five days into the fighting, President Warren G. Harding declared martial law in West Virginia and sent in the U.S. Army. The miners’ resistance soon collapsed.

The Battle of Blair Mountain took its toll on West Virginia’s mining communities for decades. But the conflict remains a source of pride for many — and is key to understanding the region’s fractious relationship with national politicians.

2. Boro’s Brief Revolution

by Eromo Egbejule (3-12-20)

In 1966, a 27-year-old Nigerian student union president named Issac Boro declared the oil-rich Niger Delta region from which he hailed a sovereign republic and himself the head of state. Nigeria had been an independent country for only six years when about 150 volunteer soldiers joined Boro to wage guerrilla war against the Nigerian government. It didn’t go well for the secessionists: After 12 days, the experiment was over, the revolutionaries were jailed, and Boro was charged with treason and sentenced to death.

Fifty-three years ago, the 27-year-old student union president of Nigeria’s first full-fledged university declared the oil-rich Niger Delta region from which he hailed a sovereign republic and himself the head of state.

WHY YOU SHOULD CARE

Right after independence, Nigeria was already playing its minority populations off each other.

“We are going to demonstrate to the world what and how we feel about oppression,” Isaac Boro told his supporters in his speech. “Remember your 70-year-old grandmother who still farms before she eats; remember also your poverty-stricken people; remember too, your petroleum which is being pumped out daily from your veins; and then fight for your freedom.” Nigeria had only been an independent country for six years, after an intense struggle against the British colonial administration.

About 150 volunteer soldiers joined the Niger Delta People’s Volunteer Force (NDPVF) to wage guerrilla war against the Nigerian government. It was the first of many secession attempts Nigeria would encounter, and it didn’t go well for the secessionists: After 12 days, the experiment was over and the revolutionaries were arrested and jailed, and Boro was charged with treason and sentenced to death.

The wave of independence and nationalism that had swept through Africa in the 1940s and ’50s began to bear fruit in the early ’60s. The year 1960, in particular, was fruitful for 17 different countries as they gained independence from Great Britain, France and a couple of other colonial masters. It has since been known as the Year of Africa.

But that struggle for independence emboldened separatist movements too. Dozens of groups sought freedom from the fragile new states they were nominally part of, and young revolutionaries like Boro — born Isaac Jasper Adaka Boro in 1938 — took that to its logical conclusion. His birthplace, Oloibiri, was the site of Nigeria’s first commercial oil discovery and first industrial oil well in the late ’50s.

His father was the village headmaster and Boro initially followed a similar path, going into teaching. But after serving as a school teacher and later as a policeman, he quit to enroll at the recently founded University of Nigeria to study chemistry. By Feb. 23, 1966, he had dropped out to devote himself full time to declaring an 11,000-square-milechunk of his country an independent state. Disillusioned by the independent government’s lack of respect for minority groups — a reflection of how the white colonizers had treated Nigerians — Boro saw an opportunity in the Niger Delta’s oil wealth to split off and allow the region to make its own decisions about its natural resources.

The turning point came in January of 1966, just weeks before Boro’s big announcement. Nigeria had its first coup: a group of majors, mostly of Igbo extraction, overthrew the civilian government of Azikiwe and Tafawa Balewa, the well-liked prime minister. Boro and many others saw the action as “an Igbo coup” and worried that the dominance of the eastern Nigerian ethnic group would bring about an “impending tribal holocaust,” says Port Harcourt-based activist, Nubari Saatah. Boro also blamed his own loss in two student government elections on such ethnic politics.

But it turned out secession was no picnic either. After 12 days of fighting, Boro was captured on March 7 and charged with treason. He was sentenced to death — but when Gen. Yakubu “Jack” Gowon became head of state later that year, he gave Boro a presidential pardon and enlisted him as an army officer. He was sent to quell another secession — Igbos in the east were attempting to split off and form their own nation, Biafra, which would eventually make a solo go of it for nearly three years.

“He noted that most of the things the minority groups were benefiting were brought by the North,” says Saatah. “All that made him join the Nigerian side.” Boro’s knowledge of the Niger Delta’s topography proved useful, but he didn’t survive the campaign, dying in 1967 at the age of 29.

Timinipre Owonaru, Boro’s second-in-command and the only surviving NDPVF member, believes that the marginalization of the delta is still on, several decades later. “What we fought for in the past hasn’t really been achieved, in the sense that we’re still in subjugation in the hands of the powers-that-be,” he says. “The inability to control and manage our resources was the reason our agitation took place and even now we’re still not controlling our resources, and that’s a big tragedy.”

Boro’s socialist revolution may have failed but it laid the path for others agitating for true resource control, like the intellectual Ken Saro-Wiwa who was hanged in 1995, and more violent militant groups that sprung up in the early 2000s. His hometown is today revered as the spiritual home of all Ijaws because of its association with Boro. In December 1998, Ijaw youths worldwide gathered there for the Kaiama Declaration, a resolution to push for increased resource control and mobilization against the environmental degradation of the delta.

“[The secession] wasn’t going to succeed and he knew it,” explains Saatah. “But it was going to show what was a possibility to both the people and the government … He wanted to draw the world’s attention to what the Niger Delta was facing.”

3. The Madrid Suburb That Went Rogue

by Melissa Kitson

In 1989, Madrid officials decided to expropriate the land of Cerro Belmonte, a humble suburb in the capital’s north — a decision that sparked an unlikely independence movement. Authorities planned to redevelop what they termed 19 “bags of urban decay,” but the residents of Cerro Belmonte refused to sell their homes. When protests didn’t work, they threatened to seek independence from the city, and so the Kingdom of Cerro Belmonte was born, a move that prompted city officials to remove the suburb from the redevelopment plan.

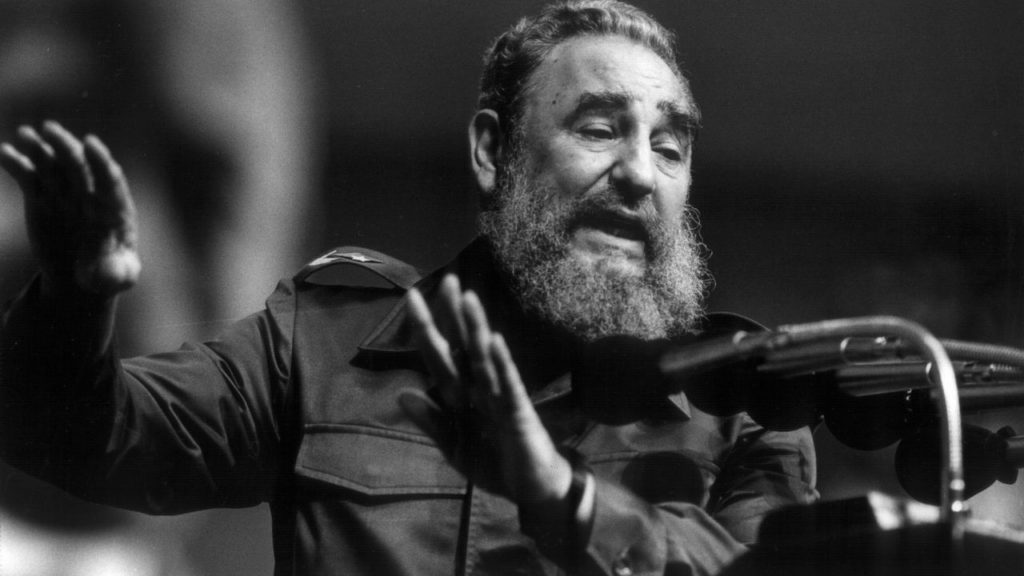

It wasn’t a call Esther Castellanos was expecting. “Mrs. Castellanos, this is the Cuban Embassy. We have good news for you. A diplomatic car will pick you up at once.”

Sure enough, a car swung past Castellanos’ home in Madrid to take her to the embassy. It was July 26, 1990, and celebrations for the anniversary of the attack on Moncada Barracks that kicked off the Cuban revolution were in full swing. Amid the raucous singing and dancing, Castellanos was told the good news: Fidel Castro had invited her to Cuba.

Castellanos wasn’t as surprised as you might expect. It was just the latest twist in a saga that had begun more than a year earlier, on March 29, 1989, to be precise. That was the day Madrid officials decided to expropriate the land of Cerro Belmonte, a humble suburb in the capital’s north now known as Valdezarza. It was a decision that sparked an unlikely independence movement— one that started local and improbably turned international.

Authorities planned to redevelop what they termed 19 “bags of urban decay,” including Cerro Belmonte, and relocate residents to surrounding neighborhoods. Cerro Belmonte’s 125 families were offered a paltry 5,018 pesetas per square meter (about $43) for their current homes in exchange for 40-square-meter apartments in nearby Vallecas and Villaverde. The City Hall brochure sold the plan as a way to “substitute centers with deficient development for new suburbs integrated in a quality urban structure.” But the residents of Cerro Belmonte weren’t buying it.

Castellanos, a 28-year-old divorce lawyer, was suspicious of City Hall’s intentions from the start. A property developer was offering 20 million pesetas for 90-square-meter apartments in an adjacent neighborhood. Castellanos told the Spanish daily El País what was commonly believed in her community: “We suspect that the expropriation of the land … could be followed by rezoning laws that allow high-rise apartments to be built.” And so Cerro Belmonte residents refused to sell their homes for less than 200,000 pesetas per square meter.

When city officials showed no interest in negotiations, the residents decided to make some noise. Literally. They staged cacerolazos, taking to the street to bang pots and pans. And during afternoon rush hour they created barricades with garbage bins, fences and placards to disrupt traffic.

When that didn’t work, the residents threatened to seek independence from the city that was trying to exploit them. “The excavators will have to drive over our dead bodies. No one is leaving the suburb,” Castellanos yelled as the machinery moved in, reported the monthly magazine El Salto.

The authorities remained unmoved by the call for secession, so Castellanos and other activists took the next logical step — they asked Cuba for political asylum. It was denied.

They weren’t expecting it to be granted. But they also weren’t expecting Fidel Castro to spring for 25 flights to Cuba. For Castellanos, it was just another way to draw media attention. At a neighborhood raffle, residents drew the 25 lucky names, including an 80-year-old man who had served in Spain’s Hitler-supporting Blue Division and a 10-year-old girl.

The locals arrived in Cuba in time for Castro’s birthday, Aug. 13, and were paraded across the island. During their seven-day Caribbean getaway, they received state honors, cigars and books, and even sat down with Castro. “We were aware that it’s all for show, but the only way of making politicians hear us is through the media,” Castellanos told the Spanish website El Español.

The publicity did little to sway Madrid. So Cero Belmonte held an independence referendum the first week of September in the home of Desideria Becerril, one of the neighborhood’s oldest residents. It was a haphazard affair with cardboard ballot boxes and handwritten voting slips, but the result was definitive — 212 votes in favor and two against. The Kingdom of Cerro Belmonte was born — a “kingless kingdom,” according to the constitution.

It was radical politics, but the movement was so small the police could do little about it, says Ángel Cuéllar, president of the Poetas Dehesa de la Villa Neighborhood Association. “They couldn’t intervene because it would have been like attacking normal people in the street.”

What followed was a rush of nationalism. Becerril’s son, Gregorio Bravo, designed the flag (a red star on a white background) and took charge of developing the kingdom’s new currency — the belmonteño, valued symbolically at 5,018 pesetas. The local punk rock band Kaduka2000 chipped in with a national anthem — “we want bread, we want wine, we want the mayor on a stick” — and a huge party was held in the local soccer stadium to celebrate ratification of Cerro Belmonte’s constitution on Sept. 12, 1990. Among other things, it promised asylum to residents elsewhere in Madrid who had been poorly treated by the city. As a final measure, founders called on the United Nations to recognize the neighborhood’s sovereignty.

At last, City Hall gave in. Officials removed Cerro Belmonte from the redevelopment plan and included it in a different one that gave locals time to negotiate better prices individually with private contractors.

“Over time the people have left, most of them were older, and there is no trace of the community. Not even the houses remain,” says Cuéllar. And with them has gone the memory of the independent Kingdom of Cerro Belmonte. “The authorities have tried to cover up what happened,” says Cuéllar. “It is just an anecdote from the past.”

4. The “Finlexit” Vote

LENIN WAS SO CONFIDENT OF MARXIST DOCTRINE AND WORLDWIDE REVOLUTION THAT HE WAS CONVINCED FINLAND WOULD COME CRAWLING BACK.

by Daniel Malloy (8-29-16)

On Dec. 6, 1917, Finland’s Parliament voted to leave post-revolution Russia, engineering its own exit from a superpower. Though it initially looked like a clean break, the departure sowed seeds for a disastrous civil war that erupted a year later amid the Continent-wide upheaval of World War I. Still, Finland has maintained a stable independence and is now a peaceful, high-income success. Other nations that were in a similar boat in 1917 — like Ukraine — remained under the Soviet thumb and went in a starkly different direction.

The bloodshed came later. But Dec. 6, 1917, was a triumph of the peaceful, democratic variety. Finland’s parliament, the Eduskunta, voted that day to leave post-revolution Russia, and Vladimir Lenin, a man with other preoccupations and ulterior long-term motives, decided not to put up a fight.

Nearly a century before Great Britain voted to “Leave,” this Nordic country — now 5.5 million strong — engineered its own exit from a superpower. Though it initially looked like a clean break, the departure really sowed seeds for a disastrous civil war that erupted a year later amid the continent-wide upheaval of World War I. Still, Finland has maintained a stable independence and is now a peaceful, high-income success. Other nations that were in a similar boat in 1917 — like Ukraine — remained under the Soviet thumb and went in a starkly different direction. But Finland was hardly a font of anti-imperialism in the early 20th century, according to University of Helsinki history professor Laura Kolbe, who says Finnish independence arrived “more or less by accident.”

The country, which is slightly larger than the U.S. state of New Mexico, had spent the previous century as a semiautonomous region of Russia; before that, it was part of Sweden. Finland developed its own bureaucratic institutions and governing system for just about everything except the army. It even had its own currency while enjoying the protection of the Russian emperor — so there was not much of an independence movement. There was also good reason for Russia to hold tight but treat Finland well, as czarist-era Prime Minister Pyotr Stolypin told the British historian Bernard Pares, noting how the Finnish border was only 20 miles from St. Petersburg, as recounted in The Finnish Civil War 1918: History, Memory, Legacy, by Tuomas Tepora and Aapo Roselius. Would England tolerate an autonomous state within its empire that close to London? A few years after he made the comment, World War I broke out, shaking all assumptions about the world order.

The Great War’s decimation helped lead to the Russian Revolution of 1917, ending centuries of imperial rule and leaving a sudden political vacuum. Torn between two powers, Finland elected a pro-German government, and its leaders declared that they wanted out from under Russia’s rule. Following the November takeover by the Bolsheviks, Finnish leaders quickly drafted and passed a Declaration of Independence.

A Finnish delegation headed by Pehr Evind Svinhufvud went to St. Petersburg to meet Lenin and ask for a clean break, which the new leader provided. Kolbe says Lenin was so confident of Marxist doctrine and worldwide revolution that he was convinced Finland would come crawling back.“Independent states, sooner or later their working class creates revolution and wants to be part of the Soviet Union,” Kolbe says. “That was his genius plan.” Lenin’s idea was not too far-fetched. Inspired by the Bolsheviks next door, Finnish socialists had declared a general strike in November, and the new independent government was not eager for compromise. The departure of Russian troops left the streets unpoliced, and the revolutionaries were emboldened by unrest throughout the region.

Finland’s four-month civil war began in January 1918, pitting the urban working-class Red Guard against the bourgeois Whites. It was also a proxy war between Russia and Germany — though the Russian troops pulled back early. There is no verified figure, but more than 30,000 people died, an astronomical sum within just a few months — many perishing in refugee camps or through extrajudicial means, not just in battle. Russians were murdered “in circumstances that can only be described as ethnic cleansing,” Tepora and Roselius write in The Finnish Civil War 1918.

The Germans were briefly in control but left by year’s end, after losing World War I. Finland was again a Soviet-Germany battlefield in World War II, but it remained independent, never giving in to Lenin’s fantasy. The working class was incorporated into the political system, and the Communist Party never gained much traction. It eventually turned into a stable liberal democracy, compared to other Russian border states. Next year marks the centennial of the “Finlexit” vote, and the government is preparing for Finland’s biggest-ever birthday party, beginning with a televised bash on New Year’s Eve. As far as birthday presents go, it would be hard to top a proposal in neighboring Norway, where leaders are considering shifting the border and offering their 4,478-foot Mount Halti summit to Finland — giving the nation a new highest peak with which to celebrate its centennial.

Daniel knows where the bodies are buried, which is why he’s been a trusted member of OZY’s PDB team while stationed in Laos and is a much-valued reporter now that he’s back in the good ol’ USA. Having been gone for just a year, the one-time NBA hopeful — those dreams got dashed when he measured up to a paltry 5’2” his freshman year in high school (though he’s 5’11” now) — is finding America a far different country than the one he left just 12 short months ago.

His wheelhouse? National politics, and he’s excited to be beating a path once again to the nation’s capital, where you can catch him schmoozing with buddies at Capitol Lounge or Iron Horse on visits, even though his home base is further south in North Carolina. But Daniel is also a sucker for true crime. Once, while working for The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Daniel was doing the graveyard cop shift when he caught an intriguing news story about a local guy who had buried a woman in his front yard. When he went knocking, Mr. Greenthumb — nope, not his real name — said he didn’t like how he’d been portrayed on television. So Daniel convinced him to talk, and the man — who had yet to be arrested or charged — spilled the beans. He had befriended an older woman, moved in with her and returned home one day to find that she had died in her sleep. Not having any money and with no way of reaching her estranged family the man decided to take matters into his own hands. Under cover of darkness, he dug a hole and buried her in the front yard. He then proceeded to cash the woman’s Social Security checks … until, that is, her long-lost son came calling with police a couple years later.

Having grown up in Alexandria, VA, covering national politics was almost inevitable. But Daniel did get away for school at UNC-Chapel Hill and for stints in Pittsburgh and Laos. While covering all things Washington for the Atlanta Journal Constitution, his calling card there wasn’t so much his written word as his voice. Daniel made a series of raps relating to Georgia state politics in 2014 that the AJC put online for a lark. Gawker poked fun at one, helping it go viral. Such was Daniel’s rap fame that even Georgia’s secretary of state greeted him as “the rapper.”

From Washington, he decamped to Laos for a year-long adventure along the Mekong River that included staying one step ahead of immigration authorities and government censors. If anyone asks, he was a writer and sometime bar manager who most certainly did not commit any journalism inside the country. Apart from skirting a few laws while overseas, Daniel claims he just has a couple of bad habits: eating unhealthily when his wife’s not looking and swearing like a sailor — the latter often coming during intense UNC basketball games. Keep an eye out for his reporting on the Trump administration and please stop asking him when the rap mixtape is coming out. You can’t just will art.

Badass Women

1. Ching Shih

by Laura Secorun Palet (4-27-16)

THE LADY PIRATE WHO TERRORIZED HER WAY TO THE GOOD LIFE

The world’s most successful buccaneer might have been Chinese — and a woman. Ching Shih instilled fear in the hearts of merchants across the China Sea in the early 19th century. During her relatively short run as a pirate lord, this ruthless and cunning woman went from being a prostitute to commanding the infamous “Red Flag Fleet.” At the height of her success, Ching Shih’s pirate armada boasted 1,600 ships, and she commanded more than 70,000 male and female pirates, spies and suppliers.

The history of piracy is full of clichés. Yet the world’s most successful buccaneer might have been Chinese — and a woman. Ching Shih, also known as Cheng I Sao, instilled fear in the hearts of merchants across the China Sea in the early 19th century. During her relatively short run as a pirate lord — about a decade — this ruthless and cunning woman went from being a prostitute to commanding the infamous “Red Flag Fleet” and sending hundreds of thousands of men into battle.

At the height of her success, Ching Shih’s pirate armada boasted 1,600 ships, and she commanded more than 70,000 male and female pirates, spies and suppliers. Her sphere of influence stretched from the waters of the South China Sea through much of Guangdong Province, and she even had spies working within the ruling Qing Dynasty.

The Qing emperor, Jiaqing, raised a large fleet of ships against her to no avail. Ching Shih was eventually offered amnesty by Jiaqing, and went on to retire at the ripe age of 35. The queen of the pirates then had a child, opened a brothel and lived a comfortable life until she died, at age 69, a wealthy aristocrat. Her name has been largely forgotten, but her legacy still lives today on the pirate-infested waters of the South China Sea.

2. Lyudmila Pavlichenko

by Fiona Zublin (3-25-17)

MEET THE ORIGINAL NAZI-PUNCHER

THE WHOLE WORLD WILL LOVE HER FOR A LONG TIME TO COME / FOR MORE THAN 300 NAZIS FELLED BY YOUR GUN. -Woodie Guthrie-

Born in what is now Ukraine, 24-year-old Lyudmila Pavlichenko joined the Soviet army in 1941 and became a sniper. She was a formidable hunter, one reputed to have killed 187 people in battle over the course of 10 weeks in 1941. After hanging up her rifle, Pavlichenko became a military historian. While once she talked openly about being proud of killing Nazis, she later admitted that her first kill was difficult — that she had trembled and wondered if her target truly believed in Hitler’s cause.

The 26-year-old Soviet sniper, donning the Order of Lenin, stood before a crowd of American reporters. It was late summer, 1942, and Lyudmila Pavlichenko was asked whether she was allowed to wear lipstick on the job. “There are no rules against it,” she said, smiling faintly, before regaling the press with tales of how she had killed 309 Nazis.

As we debate once again whether or not it’s OK to punch Nazis, Pavlichenko — aka “Lady Death” — offers a few words of wisdom from beyond the grave. “The only feeling I have,” she said when asked whether she had mixed feelings about being the most successful Soviet sniper of World War II, “is the great satisfaction a hunter feels who has killed a beast of prey.”

So how did Pavlichenko end up talking to a scrum of reporting Yanks? “The U.S.S.R. wanted a woman to show that it was a war where everybody was involved … She was available and alive,” says Amandine Regamey, an academic working on a biography of Pavlichenko. Born in what is now Ukraine, the 24-year-old Pavlichenko joined the Soviet army in 1941. When a recruiter attempted to assign the student of history to nursing duties, she presented a certificate proving her shooting prowess — skills acquired thanks to her shooting hobby — and became a sniper.

Though some academics doubt the figure of 309 kills, there’s no doubt Pavlichenko was a formidable hunter: She is reputed to have killed 187 people in battle over the course of 10 weeks in 1941, according to Sniper in Action. She was wounded three times and evacuated by submarine from the battle of Sevastopol, in which her husband, a fellow soldier, was later killed.

Having achieved notoriety for her battlefield prowess, Pavlichenko was sent to the U.S. in 1942 — possibly, Regamey says, because having a woman fronting the tour for the U.S.S.R. would shame American men into getting more involved in the war effort. During the war, the U.S.S.R. recruited thousands of women into combat roles, including an estimated 2,000 sharpshooters.

It was Pavlichenko, the first Soviet citizen received by a U.S. president, who won over the American public — and its first lady Eleanor Roosevelt, who arranged the young Soviet’s national tour. Fifteen years later, the 32nd U.S. president’s wife visited Pavlichenko’s two-room apartment in Moscow and heard her war stories once again, firsthand. Crowds of 100,000 were reported at rallies in Pavlichenko’s honor during her wartime tour, and American troubadour Woody Guthrie immortalized the famous sniper with his song “Miss Pavlichenko,” crooning how “The whole world will love her for a long time to come / For more than 300 Nazis fell by your gun.”

Pavlichenko, and the equality she talked up at the behest of her higher-ups, was inspiring to much of America’s left. The Soviet Union presented itself as a paradise of equality, where all genders and races were treated the same, and Pavlichenko represented that to many who hoped similar values would take hold in the U.S. “I send you my deep and heartfelt greetings to your country fighting for the liberation of all mankind,” Adele Young, an African-American, wrote to Pavlichenko in 1942. “Your visit here is an inspiration to us to continue our fight.”

Pavlichenko herself wasn’t an outspoken feminist. Her steely mien won people’s respect, though, and when she returned to Moscow, she was declared a Hero of the Soviet Union, the nation’s highest honor. By being an outstanding sniper and a woman, she helped open up opportunities for women in combat roles. At the onset of World War II, many women had been relegated to nursing work, but thanks to Pavlichenko and others, a women’s sharpshooting school was opened by 1943; by the time the war ended, more than 1,800 women had become Soviet snipers. Many of them weren’t as lucky as Pavlichenko, who never saw combat again: Fewer than 500 are believed to have made it through the war.

In the 1960s, the former sniper’s discourse about her life’s work changed. While once she talked openly about being proud of killing Nazis and making the world safer for her countrymen, she later admitted that her first kill was difficult — that she had trembled and wondered if her target truly believed in Hitler’s cause or had simply been sent into battle.

After hanging up her rifle, Pavlichenko returned to her studies, earning a history degree from Kiev University. She became a military historian for the Navy until retirement, long after she’d already made military history herself.

Fiona Zublin grew up in a magical Northern California forest filled with hippies and activists. She accidentally started a cult at the age of 8, and while that was obviously her real talent, she ended up wanting to be a writer instead — same storytelling, slightly better chances for respectability.

She moved on to D.C., accidentally becoming a journalist after university because she thought it’d be practical. Hush. She wound up writing about performance art, opera and the proper way to eat crickets for The Washington Post and producing breaking news at National Public Radio over the course of five years — or as they say in D.C., 1.25 election cycles — which included two presidential inaugurations, a midnight mass in the back of a bar and multiple instances of changing into a ballgown in the back of a cab (“It’s for work, I swear!”)

The romance of being a broke graduate student lured her to London, where she researched foreign correspondents at the London School of Economics and got a front-row seat to Britain’s wacky modern immigration politics. At OZY, Fiona works on the Presidential Daily Brief, writes Immodest Proposals and covers the wolves and s’mores beat. She’s part of our European team and is based in Paris, where her French is more than sufficient for what matters most: ordering pastry and occasionally sparring with strangers about American sourdough bread.

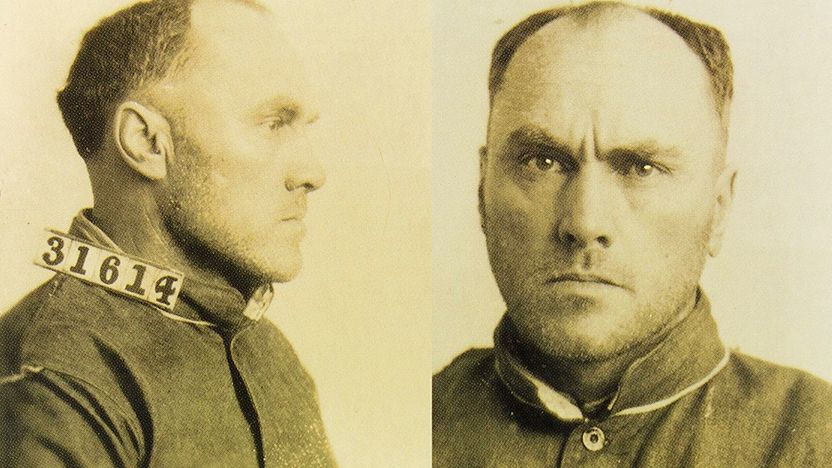

“A FELLOW CAN’T AFFORD TO HAVE NERVES IN THIS BUSINESS.”

by Dan Peleschuk (5-13-18)

Sympathizing with a sadistic Nazi propagandist is a tall order. Still, Julius Streicher’s execution in a small prison gym following his conviction on war crimes at the Nuremberg trials must have been agonizing. After the noose was snugged around his neck and the black hood pulled over his head, the infamous editor of Der Stürmer managed to get out one last “Heil Hitler!” before the trapdoor opened, and he plunged out of sight behind the black cloth hung as a privacy panel on the front of the gallows. But as the Allied military officers and eight journalists in attendance soon discovered, something wasn’t right.

The rope had failed to snap the Nazi’s neck. Instead, Streicher swung violently and groaned in pain as he struggled for air. A correspondent for the International News Service reported that the American hangman, Master Sgt. John C. Woods, disappeared behind the black cloth to rectify the situation. “I was not in the mood to ask what he did,” the reporter wrote in his Oct. 16, 1946, dispatch, “but I assume that he grabbed the swinging body and pulled down on it.”

Anyone else might have been embarrassed about botching such a high-level execution. But Woods, an almost charmingly hapless man with a checkered past, relished his role in sending 10 convicted, top-level Nazis to their deaths. The fact that he reportedly bungled at least three of the hangings — in addition to around 20 others throughout his short career — didn’t seem to bother him. “The way I look at this hanging job,” he told another correspondent that day, “somebody has to do it.”

Born in 1911, Woods was abandoned by his parents and raised by his grandparents in small-town Kansas. He dropped out of high school and, after struggling to find work, joined the Navy, only to find out that following orders apparently wasn’t for him. After going AWOL, he was caught, declared a “constitutional psychotic” and dismissed. For years, he bounced from one job to another with little success, found himself in a scandalous marriage and was busted for floating a bad check. When World War II broke out, Woods was drafted into the U.S. Army as a combat engineer; his discharge from the Navy apparently went undetected.

Then came D-Day. Woods landed in Normandy during one of the first waves of assault, according to author French MacLean, a retired Army colonel, and the bloodshed he witnessed must have shaken him — at least enough so that when the Army put out a call for a hangman, he piped up and explained how he’d once helped execute several men in Texas and Oklahoma. “Well, he was lying,” says MacLean, whose book about Woods is forthcoming. “But the Army didn’t check up, because we didn’t want to find something we didn’t want to find, or we tried to check up, and it was too hard.” Woods was promoted from private to master sergeant in one day and trained under a major for about a dozen hangings, most of them performed on American troops.

In those days, says military historian Frederic Borch, a death sentence was typical for grievous crimes such as murder and rape. It was an effective way of maintaining discipline during wartime, while also sending a clear signal to locals who were newly liberated from Nazi tyranny. “They didn’t want the French to think that they just traded one set of SOBs for another set,” says Borch, a regimental historian for the Army Judge Advocate General’s Legal Center and School in Charlottesville, Virginia. Woods found himself fairly busy: Of the 96 U.S. soldiers executed in Europe and North Africa during World War II, he hanged around 30 of them. Not all of the death sentences were carried out smoothly, MacLean says, probably due to Woods’ lack of experience.

But Woods’ crowning — if macabre — achievement came following the Nuremberg trials of October 1946. Of the 11 top surviving Nazis convicted of war crimes, 10 were sent to Woods to meet their end (two hours before his turn, former German Air Force chief Hermann Göring killed himself with a vial of potassium cyanide that had been smuggled into his cell).

The executions were not clean kills. Joachim von Ribbentrop, the foreign minister who went first, shortly after 1 a.m., took 14 minutes to die; the second prisoner, field marshal Wilhelm Keitel, choked for nearly twice as long, according to eyewitness media accounts. While those mistakes may have been accidental, MacLean believes that Streicher’s shoddy execution was intentional, arguing that the propagandist’s famous flair for the dramatic stole the scene from Woods. He also cites testimony from a lieutenant present at the scene, who saw Woods cast a wry smile during Streicher’s turn. “At an execution,” MacLean says, “John Woods wanted to, and insisted on, playing the lead actor.”

On that infamous day, the Kansas high school dropout was brimming with confidence, reportedly boasting of his efficiency in killing 10 men in just 106 minutes. “I wasn’t nervous,” he told Time magazine after the hangings. “A fellow can’t afford to have nerves in this business.” Although Woods enjoyed his brief notoriety, he died several years later from electrocution on the Pacific island of Eniwetok while serving in an engineering unit. Some believe the death was suspicious, noting the alleged presence of German scientists working on the atoll for the U.S. weapons program. Either way, his exit was certainly quicker than that of his most famous victims.

3. Julie d’Aubigny

WHEN AN AUDIENCE MEMBER QUESTIONED HER GENDER … D’AUBIGNY RIPPED OFF HER SHIRT IN FRONT OF HIM.

by Meradith Hoddinott and Fiona Zublin (1-26-20)

Julie d’Aubigny, aka Mademoiselle Maupin, was the renowned daughter of a clerk in the court of Louis XIV. Born around 1673, she was taught fencing by her father, and eventually ran away with a swordsman. The couple traveled the countryside, showing off their fencing skills to the public. Once, while attending a royal ball dressed as a man, she was challenged to three duels in a single evening — and won them all. D’Aubigny later became an opera star and inspired a French novel.

How many duels do you think you could fight in a single day? A glimpse at one badass French swordswoman in action offers a possible answer: three. After attending a royal ball dressed as a man, and romancing and then kissing another woman on the dance floor, she was challenged by three men. She proceeded to take them on one by one, and to best all three.

If you can believe it, that’s not even among the top three most improbable stories about Julie d’Aubigny, aka Mademoiselle Maupin, the renowned daughter of a clerk in the court of Louis XIV. While it’s hard to know how many of the stories about d’Aubigny are true — even her real name remains unclear, with some accounts calling her Émilie, others Madeleine and some simply “la Maupin” — legends about her have survived, reminding us that even in the 17th century, some people are born to impress.

“What’s most dizzying to me is the pace of her life,” says Kelly Gardiner, author of Goddess, a fictionalized account of d’Aubigny’s life. “Most of the more astonishing events happened before she was 20.” While researching Goddess, Gardiner visited every known location of one of d’Aubigny’s most notorious exploits and pored over primary sources for information about her wily subject. What she found: a woman who flouted social convention, class, gender, marriage and the law.

Born around 1673, d’Aubigny was taught fencing by her father, an assistant to the Count d’Armagnac. As a teenager, she was married off to a pretty boring guy who bestowed her with one of her famous names: Maupin. Predictably, d’Aubigny, who was having an affair with d’Armagnac, didn’t stick around. Instead, she found a fencing expert, known as Séranne, and ran away with him. The couple traveled the countryside, showing off their fencing skills to the public. When an audience member questioned her gender — she was just too good at sword-fighting to be a woman, you see — d’Aubigny ripped off her shirt in front of him.

Her next known lover was the daughter of a merchant, who ended up sending his girl to a convent to keep her from the insatiable d’Aubigny. She promptly enrolled in the convent too. While Gardiner hasn’t found evidence for the following story, it appears in most accounts of d’Aubigny’s life: She and her lover disinterred the body of a recently expired nun, put it in the lover’s room and set the convent on fire before fleeing.

Then, as now, body snatching was a non-non: After failing to appear in court to answer charges of kidnapping, body snatching and arson, d’Aubigny was sentenced to death. All that, and the affair with her convent girlfriend didn’t even last. One appeal to the king later, thanks to the Count d’Armagnac, and d’Aubigny was freed, after which she moved to Paris and became an opera star known as Mademoiselle de Maupin. She was “received with raptures,” according to Robert Malcolm’s biographical sketch of d’Aubigny in his 1855 Curiosities of Biography, which also claims that later in life, d’Aubigny reunited with her husband and eventually saw a priest to receive the last rites. The move to Paris happened around 1690, which would have made d’Aubigny just 17.

While an opera star, d’Aubigny continued dueling. Aside from the three duels in one night, which saw her sentenced to death again and pardoned again, she wound up in a duel with the Comte d’Albert. Stories vary — in some, the count doesn’t realize that his opponent is a woman; in others, he’s a crude would-be Romeo — but the outcome is always the same: D’Aubigny wounds the count, then allegedly nurses him back to health, thus beginning a lifelong friendship. All this dueling, though, was still illegal, so d’Aubigny fled to Belgium, where she became the mistress of the elector of Bavaria. When he grew weary of her and offered her 40,000 francs to leave, d’Aubigny threw the money back at him and, according to Malcolm’s Curiosities of Biography, “kicked him down stairs.”

By some accounts, d’Aubigny spent time as a maid in Madrid before returning to Paris, where she fell in love with the famously beautiful Madame la Marquise de Florensac. The couple reportedly played house for two years, until the latter died suddenly. While d’Aubigny’s cross-dressing and open affairs with women were exceptional for the time, Gardiner notes that they weren’t unheard of — there are records of lesbian couples living together, and other women also lived by the sword.

After her lover’s death, d’Aubigny, still in the opera, lived for another few years, likely into her mid-30s. The exact cause of her demise is unknown. Most contemporary accounts of her life, Gardiner explains, were written by men offended by her actions and by the fact that d’Aubigny always won. She also inspired an 1835 French novel, Théophile Gautier’s Mademoiselle de Maupin, in which a character named Madeleine de Maupin seduces both a young man and his mistress while in various disguises.

“She was a star,” Gardiner says, noting the difficulty of parsing fact from fiction when it comes to d’Aubigny. Many of the stories were told in “tabloid pamphlets, posters and newssheets,” stories that people sang songs about in the streets and taverns. Rumors quickly spread, Gardiner adds: “Imagine trying to make sense in a few hundred years of news reports written now about performers.”

4. The U.S. Women’s National Soccer Team

by Sean Brazswell

They started off largely ignored, with no budget and no media coverage of their dominant play. They became global superstars with their 1999 World Cup victory, powered by Mia Hamm’s brilliance and Brandi Chastain’s sports bra celebration seen round the world. As their on-field triumphs continue along with their epic fight for equal pay, the women of U.S. soccer are an American tale unlike any other.

In the summer of 1985, the first U.S. women’s national soccer team made their debut in Italy. The ragtag group, cobbled together in less than a week and with a shoestring budget, little time to practice, and hand-me-down uniforms, struggled to keep up with their international competition. But their perseverance and their love of the game laid the groundwork for the winning team culture that fueled the championship teams of the 1990s.

5. Lumina Sophie dite Surprise

LUMINA ORGANIZED A GROUP OF PÉTROLEUSES — FEMALE INSURRECTIONISTS WHO SHARED A NAME WITH THE LEGENDARY FIGHTING WOMEN OF THE PARIS COMMUNE JUST MONTHS EARLIER.

by Fiona Zublin (9-29-18)

For France, Joan of Arc is the ultimate national heroine. But French-controlled Martinique has another young female heroine, Lumina Sophie dite Surprise. Lumina was a revolutionary leader who, despite being pregnant, organized a movement in 1870 against those who would oppress the island’s Black population. During a revolution that lasted only five days, Lumina led a group in torching plantations where their ancestors had worked as slaves before being arrested and sentenced to life in prison with hard labor.

For France and many of its former overseas colonies, Joan of Arc is the ultimate national heroine — the young woman who stepped out of nowhere and, armed mostly with the white-hot fire of belief, led her people to victory and freedom. But Martinique has another heroine, who stepped out of the bayou armed with the white-hot fire of … well, fire: Lumina Sophie dite Surprise.

Lumina is remembered, when she is remembered, as one of the leaders of her island’s 1870 insurrection. Perhaps it’s harder for France to idealize her story, seeing as European colonists are the villains in it. Or maybe racism persists in French culture — as evidenced by protests when a mixed-race teenager was chosen earlier this year to portray Joan of Arc at an annual pageant.

“For me, she was like a Creole Joan of Arc,” says Suzanne Dracius, who authored a play about Lumina’s life after an account of the 1870 insurrection found its way to her from a bookseller’s stall by the Seine. “There are so many similarities between them: young women who left their serene little universes to put themselves in danger and fight. But there are differences: Lumina was pregnant. And Lumina read newspapers.” But when Dracius visited a history museum in Martinique, Lumina’s name was barely mentioned. Dracius’ 2005 play, Lumina Sophie dite Surprise, revitalized interest in her as a heroine. Now there are songs by local artists about Lumina, as well as a high-rise and a high school named after her.

Nicknames were common in Martinique in the immediate aftermath of slavery, reflecting a racist tradition where slaves were given only first names and numbers, and Lumina’s has become part of her moniker in modern times — all one phrase tumbling out, Lumina Sophie dite Surprise: Light, Wisdom, called Surprise. It would be difficult to be more on the nose, unless you were to add something equally mellifluous that means an “ahead-of-her-time renegade who wasn’t afraid to literally burn shit down.”