JOURNAL OF SOCIAL WELFARE AND FAMILY LAW. Routledge, Taylor & Francis Grp.

2020, VOL. 42, NO. 1, 92–105 LINK w/IMAGES & Tables

https://doi.org/10.1080/09649069.2020.1701941 Check for UPDATES

U.S. child custody outcomes in cases involving parental

alienation and abuse allegations: what do the data show?

Joan S. Meier

George Washington University Law School, Washington, D.C., USA

ABSTRACT

Family court and abuse professionals have long been polarized over

the use of parental alienation claims to discredit a mother alleging

that the father has been abusive or is unsafe for the children. This

paper reports the findings from an empirical study of ten years of

U.S. cases involving abuse and alienation claims. The findings confirm

that mothers’ claims of abuse, especially child physical or

sexual abuse, increase their risk of losing custody, and that fathers’

cross-claims of alienation virtually double that risk. Alienation’s

impact is gender-specific; fathers alleging mothers are abusive are

not similarly undermined when mothers cross-claim alienation. In

non-abuse cases, however, the data suggest that alienation has

a more gender-neutral impact. These nuanced findings may help

abuse and alienation professionals find some common ground.

Introduction

Protective parents and domestic violence professionals have long asserted that courts dealing with child custody and their affiliated professionals frequently deny true claims of adult partner or child abuse and instead punish parents (usually mothers) who allege domestic violence, child physical or sexual abuse, or seek to limit the other parent’s child access for any reason.

Anecdotal reports1 have suggested that courts are even less receptive to mothers’ claims of child physical or sexual abuse than their claims of partner violence, and that many mothers alleging abuse – especially child abuse2 – are losing custody to the allegedly abusive father.

Studies describe the severe and damaging consequences for children forced by courts to be with fathers they or their protective parents claimed were harmful (Silberg et al. 2013). Sadly, there is even a growing list of U.S. children killed by a parent; as of the time of writing, the website for the Center for Judicial Excellence lists 704 children killed by a separating or divorcing parent; researchers have verified that at least 101 of the children were not protected by family courts despite requests (Center for Judicial Excellence 2019). A particular target of critique has been courts’ reliance on ‘parental alienation’ to refute mothers’ claims of abuse by fathers (Bruch 2001, Meier 2009, Milchman 2017, Neilson 2018).

An adaptation of the ‘parental alienation syndrome’ (‘PAS’) coined by CONTACT Joan S. Meier jmeier@law.gwu.edu This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article. JOURNAL OF SOCIAL WELFARE AND FAMILY LAW 2020, VOL. 42, NO. 1, 92–105 https://doi.org/10.1080/09649069.2020.1701941 © 2020 Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group Richard Gardner (1992).

Parental alienation, while lacking any universal definition, embodies the notion that when a child (or the primary parent) resists contact with the non-custodial parent without ‘legitimate’ reason, the preferred parent is ‘alienating’ the child, due to her own anger, hostility or pathology (Johnston and Kelly 2004, Zaccour 2018).

Although PAS itself – which Gardner defined as a mother’s false claim of child sexual abuse to ‘alienate’ the child from the father – has been largely rejected by most credible professionals (Meier 2009, p. 5, Thomas and Richardson 2015), alienation theory writ large continues to be the subject of a growing body of literature, and is frequently relied on in U.S. family court cases. Gardner’s ‘parental alienation syndrome’ treated mothers’ abuse claims as specious and illegitimate.

While some contemporary alienation proponents make little effort to distinguish alienation from PAS and utilize the identical criteria (Bernet 2017, Baker 2019, Children and Family Court Advisory and Support Service 2019), others have endeavored to distinguish their view by rejecting PAS’ attribution of blame solely to the preferred parent, acknowledging that there are typically multiple causes of children’s resistance to a parent post-separation, including the disliked parent’s own behaviors, and naming ‘legitimate’ cases ‘estrangement’ (Saini et al. 2016, p. 424, Drozd and Oleson 2004).

Despite the more refined discussions of parent rejection in some literature, however, these nuances rarely if ever appear in practice. When children reject contact, the concept of alienation is still regularly used to focus blame on the preferred parent, as did Gardner and PAS.3

Other causes of a child’s rejection of a parent, including direct abuse, witnessing their mother’s abuse, or other forms of bad parenting or injuries to a child’s affection (Johnston 2005, p. 762), are routinely ignored. Nor, after reviewing and litigating hundreds of cases, has this author ever seen a court order a disfavored parent (particularly a father) to take action to repair their own relationship with their child. Instead, a child’s favored parents (typically mothers) are expected to prioritize improving the other parent’s relationship with the child.4

In short, the widespread experience of protective parents and their experts and advocates has been that no matter what term is used – ‘alienation’ alone or PAS, the outcome is the same: Both are used to discredit and criticize a mother who is reporting domestic violence and/or child abuse in the custody context, and to ignore children’s expressions of distress about a parent. Despite extensive litigation, (DV LEAP Legal Resources), scholarship (Bruch 2001, Meier 2009, Milchman 2019), and the training (DV LEAP Training Materials, NIJDV) of judges and other professionals by domestic violence professionals, the gulf between family court professionals and abuse professionals has continued to widen. Informed by their focus on parental alienation, family court professionals and researchers reject the above critiques, asserting instead that domestic violence professionals are too credulous, that many mothers’ abuse clams are actually false or exaggerated, and that abuse professionals do not grasp the reality and perniciousness of parental alienation (Bala 2018, slide, p. 10), which they liken to psychological child abuse (Kruk 2018).

Some alienation professionals also assert that fathers commit parental alienation at least as often as mothers – arguing that therefore alienation is not a gender-biased theory5 (Gottlieb 2019).

The two groups generally lack both respect for and trust in each other. JOURNAL OF SOCIAL WELFARE AND FAMILY LAW 93

At bottom, the two fields differ fundamentally on (i) whether it is true that courts frequently disbelieve legitimate abuse claims by mothers and wrongly strip them of custody, subjecting children to ongoing risk; (ii) the degree to which parental alienation labels are the vehicle for such treatment; and (iii) whether gender bias influences these dynamics.

For all these reasons, obtaining objective data on what is really going on in family courts has become critical. Neutral data has the potential to speak to both groups as well as the wider public, and to establish an objective description of reality. Although such data-gathering cannot tell us whether particular abuse or alienation claims were true, an empirical picture can shed light on family court patterns of adjudication in such cases, including potentially the role of gender (Meier and Dickson 2017).

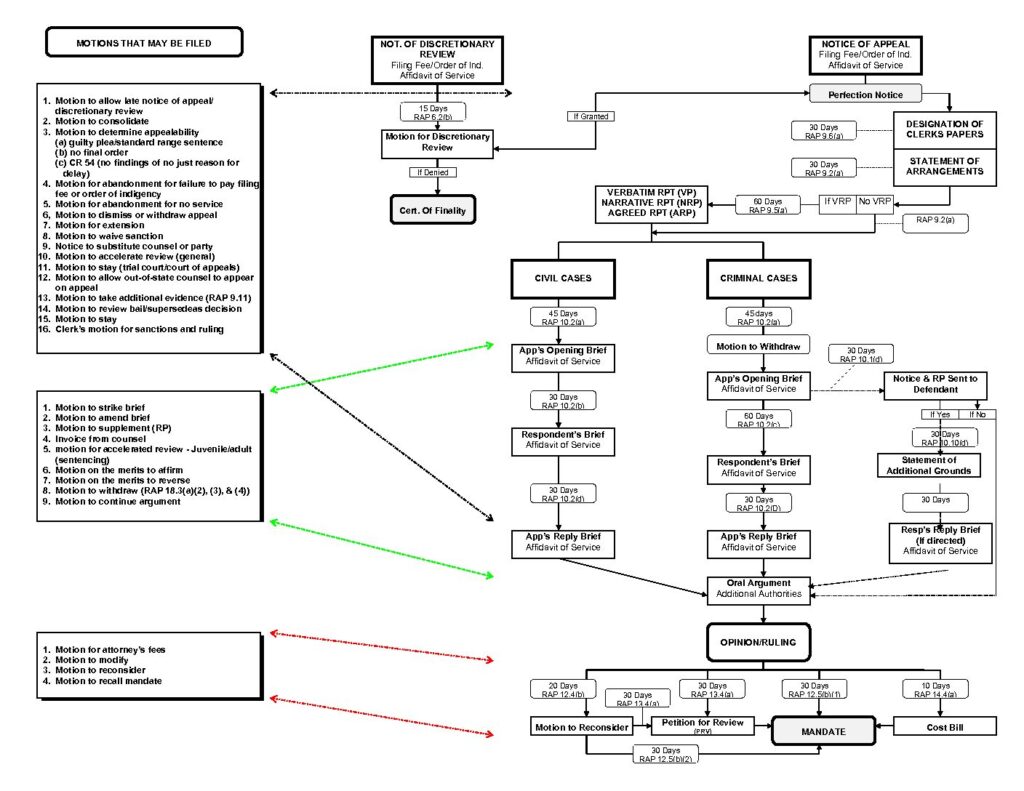

After completing a pilot study of 240 cases in 2012, (Meier and Dickson 2017), the author and a team of experts6 applied for federal funding to expand the pilot research.7 In 2014, the U.S. National Institute of Justice awarded a grant to support the ‘Child Custody Outcomes in Cases Involving Parental Alienation and Abuse Allegations Study’ (‘Family Court Outcomes (FCO) Study’ or ‘Study’).

Previous studies have examined non-protective custody outcomes in cases with domestic violence claims within particular jurisdictions (Zorza and Rosen 2005), but none has specifically discussed or analyzed courts’ responses to child abuse claims, nor have any provided a national picture. The Study was therefore designed both to provide a national empirical overview to assess whether the problems identified in prior localized research are systemic and pervasive, and to gather information about the impact of child abuse as well as domestic violence claims. Description of study

The Study sought to develop empirical measures of

(i) the rates at which courts credit (i.e. believe)8 different types of abuse and alienation allegations raised by either parent against the other;

(ii) the rates at which parents win/lose the case, or lose custody when alleging any type of abuse against the other parent;

(iii) the impact of alienation claims/defenses on (i) and (ii) above; and

(iv) the impact of gender on (i), (ii), and (iii) above. That is, do the rates of crediting of abuse, wins, or custody losses vary for mothers and fathers when one accuses the other of abuse or alienation?

Because there are thousands of state family courts across the United States, the only way to gather national data on family court outcomes is to examine judicial opinions posted online. Fortunately, by 2015, most appellate court opinions were available online, and, as we learned, so were a surprising number of trial court opinions. [edit note: Appellate courts typically do not consider the merits, but defer to the trial court judge unless there’s overwhelming evidence/indications of abuse of discretion. They look for procedural errors and errors in interpretation of law. The researchers did not weigh differences in income/representation of the litigants, education levels, other factors contributing to confirmation biases of judges, and other factors inherently embedded in the judge such as gender, experience, age, and socioeconomic background. The analysis is defective for failure to adequately weigh the myriad factors in the background noise, making it virtually impossible to extract the tune from the ‘data’ if one can call .it that. The study itself is rife w/confirmation biases]

The search for published opinions covered the 10-year period from 1 January 2005 through to 31 December 2014. [OLD!] The Study collected all cases reported online that matched these criteria within a 10-year period, thereby providing a complete ‘census.’ Two law graduates triaged over 15,000 cases that were identified by our comprehensive search string, and then coded, in detail, the 4338 cases that matched the Study’s criteria. Far more information was coded than could be analyzed during the Study time-frame; the complete dataset is available to future researchers for secondary analyses. Cases were coded for claims of partner abuse (DV), child physical abuse (CPA) and child sexual abuse (CSA), as well as mixed forms of abuse, i.e. DV + CPA or CSA (DVCh) and CPA + CSA (CPACSA).9 Altogether, these five categories constitute the coded abuse 94 J. S. MEIER types.

Courts’ acceptance or rejection of abuse and alienation claims, and their custody orders were coded. Regarding case outcomes, this paper focuses on custody switches, in which one parent started with primary custody or physical care of the children and the court switched custody to the other.

Limitations

The core limitation of the Study stems from its data source: since most trial courts do not publish their opinions (online or otherwise), the majority of the opinions analyzed were appellate decisions. This means that the dataset over-represents cases that are appealed and under-represents non-appealed cases. Fortunately, because our dataset netted hundreds of trial court opinions online, primarily from four states, we were able to do some comparisons.

We found that mothers losing custody were over-represented in the appeals [Yes, they normally have less $ to acquire competent representation.]; there were lower custody loss rates among the non-appealed cases. This should not be surprising. Otherwise, there was little difference between the cases that were and were not appealed. The second limitation is that the Study did not and could not review the facts and assess the correctness of courts’ rulings; some may have been justifiable in the light of facts unknown to us.

Nonetheless, the Study provides an accurate picture of general outcomes and trends when abuse and alienation are claimed, which can be compared to existing anecdotal and scholarly depictions of what happens in these cases. [The study is too old and too dull to reveal any trend based on the cited factors any more than fishing in a septic tank is going to reveal where the best fishing hole lies.]

The final limitation is that the data itself – judicial opinions – is imperfect, because some opinions may not mention allegations of abuse or alienation which could have been raised at some point, but had ‘fallen out’ along the way. Our comparisons of the ‘alienation’ and ‘non-alienation’ and ‘non-abuse’ cases are subject to that caveat; however, this data does reflect judges’ views of these allegations when they deem them significant enough to report in the opinion.

Findings [Lies, damn lies…and then, ‘statistics!]

The bulk of quantitative analyses discussed herein consist of simple frequencies, e.g. percentages of claims of abuse that were believed, and percentages of mothers who lost custody when alleging different types of abuse, when alienation cross-claims were or were not made. Regression analyses were brought to bear for selected purposes, most pertinently here, to examine gender bias.

This article focuses primarily on findings related to cases where a mother accused a father of abuse. There were some – although not many – cases where the genders were reversed. Where possible those reverse cases were analyzed for purposes of a gender comparison.

The following reports the Study’s findings on

(1) courts’ crediting of different types of abuse claims and custody switches from mothers to fathers;

(2) the impact of parental alienation cross-claims on crediting of abuse and custody switches; and

(3) some key findings related to gender bias and gender parity.

Outcomes in simple abuse cases (No alienation cross-claim)

There were 1946 cases where abuse was alleged by a mother against a father, and he did not cross-claim alienation. JOURNAL OF SOCIAL WELFARE AND FAMILY LAW 95

Crediting of abuse claims

Several conclusions can be drawn from the data in Table 1:

First, looking at mothers’ claims of abuse, less than half (41%) of any type of abuse claims are credited. That women’s claims of abuse are believed less than half the time will surprise many readers. Moreover, mothers’ claims of child abuse are credited even less. The odds of a court crediting a child physical abuse claim are 2.23 times lower than the odds of its crediting a domestic violence claim (CI 1.66–2.99).

Overall, child sexual abuse is rarely accepted by courts (15%). [Extraordinary claims require extraordinary proof.] Mothers’ custody losses Consistent with the above findings on courts’ skepticism toward mothers’ claims of abuse, the data show that mothers reporting a father’s abuse lost custody in 26% (284/ 1111) of cases.

Broken down by type of abuse alleged: 10

Again, these data do not prove that these custody reversals were ill-advised; the data tells us nothing about why the courts deemed the mothers to be worse parents than the fathers accused of abuse, nor how severe any credited abuse was. However, the experiences of myriad lawyers, advocates and litigants in custody/abuse cases is that courts and ancillary professionals frequently react to mothers’ claims of paternal abuse – particularly child abuse – with hostility and criticism (Meier 2003, Meier and Dickson 2017).

It is likely, therefore, that many of these mothers were penalized with loss of custody at least in part because they reported the father to have abused themselves or their children, and the court did not believe them. Remarkably, a fair number of mothers lost custody even when the court credited the father’s abuse:

Table 1. Rates at which courts credited mothers’ claims of fathers’ abuse. Domestic violence (DV):

45% (517/1137)

Child physical abuse (CPA):

27% (73/268)

Child sexual abuse (CSA):

15% (29/200)

Mixed DV with CPA or CSA (DVCh):

55% (165/302)

Mixed CPA & CSA (CPACSA):

13% (5/39)

Any:

41% (789/1946)

Table 2.

Custody switch to father by type of abuse mother alleged.

DV:

23% (149/641)

CPA:

29% (39/135)

CSA:

28% (37/131)

DVC:

26% (48/182)

CPACSA:

50% (11/22)

Any:

26% (284/1111)

Table 3.

Custody switch to father when courts credited fathers’ abuse.

DV:

14% (43/303)

CPA:

20% (7/35)

CSA:

0% (0/23)

DVC:

13% (13/103)

CPACSA:

0% (0/4)

Any:

13% (63/468) 96 J. S. MEIER

The good news in these data (Table 3) is that when courts believe a father has sexually abused his child, they do not switch custody from the mother to the father. However, overall, the data in Tables 2 and 3 powerfully affirm the reports from the field, that women who allege abuse – particularly child abuse – by a father are at significant risk (over 1 in 4) of losing custody to the alleged abuser. [Inter alia: Women who do allege child abuse prevail 3/4ths of the time.]

Even when courts find that fathers have abused the children or the mother, they award them custody 13% of the time. [This implies other critical factors may weigh on the judge’s mind, e.g. whether the mother is fit or able to care for the child.] And in cases with credited child physical abuse claims, abusers still win custody 20% of the time (Table 3).

It is also notable that when mothers allege mixed types of child abuse (both sexual and physical) their custody losses increase dramatically, from under 30% up to 50% (Table 2). In effect, mothers have 2.5 times the odds of losing custody when alleging both forms of child abuse than when they allege child sexual abuse alone.11

It is not clear what accounts for this: A child sexual abuse penalty (Meier and Dickson 2017) would be explainable by the well-known particular skepticism and hostility of courts and professionals toward such claims (Id.). But the data in Table 2 indicate that custody losses are about equivalent when mothers allege child sexual abuse as when they allege child physical abuse: It is only when they allege both that their custody losses skyrocket.

Paradigm cases with cross-claims:

(mother alleges abuse, father claims alienation)

Crediting of abuse

There were 669 cases in which one parent made an alienation12 claim against the other. In 312 of these there were cross-abuse-and-alienation claims. Of these, 222 met our definition of paradigmatic cases: where mothers accused fathers of abuse and fathers accused mothers of alienation.13

In these cases, mothers’ abuse claims were credited at even lower rates than in the non-alienation cases discussed above: The relative rates of crediting of abuse claims in alienation and non-alienation cases in Table 4 and Figure 1 below show that courts are even less likely to credit abuse claims when fathers invoke parental alienation.

The drop in crediting of abuse is even more significant when it comes to child abuse (from 27% to 18% for CPA and from 15% to 2% for CSA) (see Tables 2, 4, Figure 1). Child sexual abuse, in particular, appears to be virtually impossible to prove (only 1 case out of 51 was believed) when a father defends with an alienation claim (Table 4).

Overall, the findings in Tables 2, 4, and Figure 1 indicate that:

Table 4. Rates at which courts credited mothers’ abuse claims when fathers claimed alienation, by type of abuse.

DV: 37% (28/76)

CPA:

18% (4/22)

CSA:

2% (1/51)

DVCh:

31% (17/55)

CPACSA:

5% (1/18)

Any:

23% (51/222)

JOURNAL OF SOCIAL WELFARE AND FAMILY LAW 97

● When fathers cross-claim alienation, courts are more than twice as likely to disbelieve mothers’ claims of any type of abuse than if fathers made no alienation claim; and

● When fathers cross-claim alienation, courts are almost 4 (3.9) times more likely to disbelieve mothers’ claims of child abuse than if fathers made no alienation claim.

Custody losses

There were 163 cases in which it could be determined that mothers had physical possession of the children at the outset of the litigation and raised abuse claims in court, and fathers claimed that mothers were alienating. Similar to the above data on courts’ rates of crediting of abuse, fathers’ alienation cross-claims significantly increase the rate of courts’ removals of custody from mothers.

Table 5 shows rates of custody losses when fathers’ cross-claimed alienation.

Figure 2 compares rates at which mothers lose custody in cases with and without an alienation claim by the father:

As Table 5 (and Figure 2) indicate, when fathers claim alienation, the rate at which mothers lose custody shoots up from 26% to 50% for any abuse allegation. That is, fathers’ alienation claims roughly double mothers’ rates of losing custody driven primarily by child abuse cases.

Not surprisingly, when courts credit the alienation claim, rates of maternal custody losses increase more drastically, from an average of 26% where there is no alienation claim, to 50% where alienation is claimed, to 73% where alienation is credited by the court:

DV CPA CSA DVCh CACSA

Alien. Cases 0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60%

Non-Alien. Cases 45% 29% 15% 55% 13%

Overall, courts credited only 23% of mothers’ abuse claims in ALIENATION cases Comparison of Abuse Crediting with and without Alienation defenses 37% 18% 2% (1/51) 31% 5% (1/18) Figure 1. Comparison of Abuse Crediting with and without Alienation defenses.

Table 5. Mothers’ custody losses when father claims alienation.

DV: 35% (20/57)

CPA: 59% (10/17)

CSA: 54% (19/35)

DVCh: 58% (25/43)

CPACSA: 64% (7/11)

Any: 50% (81/163)

(98 J. S. MEIER)

Again, we see in Table 6 that the mixed child abuse (CPACSA) allegations are the most disastrous for mothers, when courts believe they are alienators: Every one of them lost custody to the alleged abuser.

Finally, while the numbers are small, the impact of credited alienation is apparent in cases where both abuse and alienation were credited by the court. Even when courts believe a father has abused a mother, if they also believe the mother is alienating, some mothers still lose custody to the [allegedly] abusive fathers. In other words, in these cases [alleged] alienation trumps abuse.

As Table 7 indicates, the zeros for credited child physical or sexual abuse show that no courts were prepared to believe that both a father’s child abuse and a mother’s alienation were true.

[Why in the f**k not? It’s not like they’re mutually exclusive!]

Table 6. When courts credit fathers’ alienation claims.

Type of Abuse Alleged

Mother Lost Custody

DV: 60% (15/25)

CPA: 59% (10/17)

CSA: 68% (13/19)

DVCh: 79% (19/24)

CPACSA: 100% (6/6)

Any: 73%

(60/82) 0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70%

Comparison of Mothers’ Custody Losses with and without Alienation Defense

29% 59% (10/17) 23% 35% 26% 28% 50% 64% 54% (8/12) 58% 50% 26%

Figure 2. Comparison of mothers’ custody losses with and without alienation defense.

Table 7. When mother is found to be alienating and father is found to be an abuser.

Type of Credited Abuse Mother Lost Custody

DV: 29% (2/7)

CPA: 0% (no cases where both abuse & alienation were credited)

CSA: 0% (“ “)

DVCh: 57% (4/7)

CPACSA: 0% (no cases where both abuse and alienation were credited)

Avg: 43% (6/14)

JOURNAL OF SOCIAL WELFARE AND FAMILY LAW 99

Selected gender comparisons14

While additional gender analyses will be forthcoming, the following gender comparisons provide powerful insight into the dynamics of gender in family court cases involving abuse and alienation.

Alienation’s use is generally highly gendered First, fathers’ and mothers’ rates of custody losses differ significantly when one or the other alleges alienation: Across all alienation cases (both with and without abuse claims), when a father alleged a mother was alienating they took custody from her 44% of the time (166/380). When the genders were reversed, mothers took custody from fathers only 28% of the time (19/67). [There’s no showing of cause and effect here. The fathers may have had better representation.] This means that when accused of alienation, mothers have twice the odds of losing custody compared to fathers. [Not necessarily–lying w/statistics and a false, straw man, argument.]

Second, narrowed down to the cases where one party alleged abuse and the other defended with alienation, mothers accused of alienation lost custody to the fathers they accused of abuse even more: 50% (81/163) of the time. Fathers who were accused of alienation by the mother they accused of abuse lost custody only 29% (5/17) of the time, but this is not a statistically significant result due to the relatively low numbers. [It could also be a result of the father having better representation along w/a host of other pertinent factors.]

In some contexts alienation is gender-neutral. Mothers and fathers fared equally in several circumstances: First, when a parent’s claim of alienation was credited (across abuse and non-abuse cases) mothers and fathers lost custody at identical rates (71%). More broadly, win15 rates were also identical (89%) for mothers and fathers when the other parent was found to have committed alienation. Second, and notably, virtual parity is apparent in the non-abuse alienation cases, where win rates are 58% (fathers) and 56% (mothers).

In contrast, when abuse and alienation are cross-alleged, this parity disappears16 (fathers win 66%; mothers 52%).

Discussion

The presence of a substantial number of alienation cases without abuse claims, and the apparent gender parity in those cases, suggest a nuanced, compelling, and ‘something-for -everyone’ potential explanation for how alienation operates in custody litigation.

First, the surprising presence of more alienation cases without abuse claims (357) than with abuse claims (312) in such a comprehensive dataset supports alienation specialists’ insistence that alienation is a problem in itself, not just a defense to abuse claims. Moreover, the apparent gender neutrality in courts’ handling of these non-abuse cases corroborates similar assertions that the alienation construct need not be intrinsically gender-biased. At the same time, however, the gendered outcomes in alienation cases where abuse is alleged strongly support the critiques of the domestic violence and protective parent fields, that when mothers report abuse in family courts, fathers’ cross-claims of alienation create an extraordinarily powerful thumb on the scale against serious consideration of the abuse. [Perjury and differences in representation do not lend themselves to statistical analysis. Moreover, the Family Court is incompetent and disinclined to conduct a genuine search for the truth.]

The fact that the same dynamic does not appear when the genders are reversed, i.e. fathers do not see a statistically significant reduction in the crediting of their abuse claims when mothers cross-claim alienation, supports the complaint that alienation in (100 J. S. MEIER) abuse cases is indeed deeply gendered and, it appears, weaponized to deny mothers’ abuse claims against fathers. [No more than the specious and suborned allegations against fathers of DV and child abuse]

The continued influence of PAS in alienation discussions is evident in several findings from this Study: First, the bias against women but not men in abuse/alienation cases is consistent with the stereotypical roots of the PAS theory, which framed the problem as a pathology of vengeful ex-wives falsely alleging abuse (see also Sheehy and Boyd 2020, Rathus 2020).

Second, given that PAS characterized mothers as falsely or pathologically accusing an innocent father of child sexual abuse, it is not surprising that alienation allegations continue to be particularly powerful in application to precisely those cases, and by extension, to child physical abuse.

As shown in Table 2 above, in only one out of 51 cases where a mother reported child sexual abuse and a father claimed alienation was the mother’s allegation considered valid by the court. Virtually the same finding appears in Canadian research (Sheehy and Boyd 2020).

While it is possible that some courts were right to reject a child sexual abuse claim, there is objective reason to suspect they were wrong more often than not. [Suspicions are no basis for deliberations nor reasonable argument.] Outside research undertaken by impartial researchers [Name them. Cite the studies. Moreover, a genuine search for the truth does not lend itself to mathematical extrapolations nor statistical analysis.] indicates that child sexual abuse claims in custody litigation are considered valid – even by conservative evaluators – 50-72% of the time (Thoennes and Tjadedn 1990, Faller 1998, Trocmé and Bala 2005). [Do they have a truth thermometer? I want one]

Intentionally false allegations are even rarer (Id.). [How is this known? How could it possibly be known?] The Study’s findings, therefore [False premise assumption], support women’s widespread complaints that custody courts are punishing them for raising child abuse by refusing to protect – and thereby endangering – genuinely at-risk children. [You get as much justice as you can afford and it’s imperfect to begin with…least of all in Family Court. The U.S. Supreme Court has ruled litigants are not entitled to a perfect trial, only a fair one. The Family Court can’t even manage that. Abolish it.] [What finding? Do you mean premise?]

We should all be able to agree that where abuse is real, children must be protected. [If it’s factual, try it in criminal court w/meaningful due process and a jury. Family Court is the wrong forum to try such allegations.] This finding [What finding? Do you mean premise?] alone should mobilize courts and other personnel involved in assessing, at minimum, child sexual abuse claims, to revisit their approaches. [That’s what criminal courts are for.]

Third, the striking finding (Table 7) that no court found both alienation and child abuse by the two opposing parents is consistent with PAS theory, which was built around false abuse claims, and asserted that true abuse meant there could be no parental alienation (Gardner 1992). [Agreed. They’re not mutually exclusive. PAS is child abuse as surely as DV.]

Ironically however, non-syndrome alienation is now more often defined without reference to false abuse claims, as simply one parent’s efforts to turn the child against the other parent (Bernet 2017, Bala 2018). Consistent with this wide-open concept, leading alienation experts are now touting ‘hybrid’ cases, suggesting that even where one parent is abusive, the other may also be alienating (Drozd et al. 2011, p. 28, 37, Bala 2018, slide, p. 9). The clear implication is that, in these cases, a parent’s abuse should be balanced against a protective parent’s supposed alienation. [Uh, yeah–they’re both forms of child abuse and PAS may be the more pernicious.]

As Lapierre et al. (2020) state: “domestic violence [is now treated] as a context that fosters the emergence of ‘alienating behaviors’’’. Unfortunately, the ‘hybrid’ concept is likely to perpetuate the misuses [Misuse? It is what it is.] of alienation to deny the implications – if not the fact – of abuse. Inviting courts to criticize protective parents for ‘alienating’ behavior inevitably undermines focus on the abuser, [Alienating behavior is inconsistent w/protective behavior. It is an extension of the adversarial barbarity in the Family Court forum.] while maintaining pressure even on parents who were abused or legitimately seek to protect a child, to remedy the abuser-child breach. After all, if courts are told that ‘yes, he hit the child and abused the mother, but she is over-reacting, criticizing him and sharing her irrational fear with the child,’ experience suggests that her ‘alienation’ will be seen as the more important problem (Sheehy and Boyd 2020; Lapierre et al. 2020, describing a case that ‘started with domestic violence and ended up with parental alienation’). [Don’t denigrate the other parent around the child or allow others to do so.]

This prediction is supported by the Study’s finding that, in 43% of cases where courts found both that (JOURNAL OF SOCIAL WELFARE AND FAMILY LAW 101) a father abused the mother and the mother was also alienating, the mother lost custody to the abusive father (Table 7).

So-called ‘hybrid’ cases aside, the Study’s clear indication that alienation allegations are widely used to deny abuse claims should be deeply concerning [They are a collateral form of attack in a Family Court deeply rooted in trial by combat w/o the protections of due process or a jury.] to all who care about children’s well-being and safety. [The genuinely concerned don’t denigrate the child’s parent around the child.]

Even experts in the alienation field have acknowledged that neither theory nor practice adequately differentiates between cases of illegitimate alienation from those where a child is ‘legitimately’ estranged (Saini et al. 2016, pp. 417–18, 423, Milchman 2019).17

This recognition logically implies that alienation can easily be misused to deny actual abuse or other destructive parenting; with one recent exception. To date, there has been very little attention paid to this problem by the alienation field (Warshak 2019). Similarly, that field’s acknowledgment that a child may resist contact for legitimate reasons stemming from the disfavored parent’s conduct should logically elicit calls for courts to address that conduct when concerned about a relationship breach.

This author is aware of no such discussion in the alienation literature. Both these lacunae may help explain abuse professionals’ distrust of alienation professionals. Logic and other thoughtful scholars18 urge that, if a parent has caused a child’s rejection or discomfort, particularly by abusing the child or other parent, addressing the breach in relationship should start with that parent’s conduct and that parent’s remediation. [The Family Courts are lawless, thus incapable and incompetent to administer such an approach. If there is factual child abuse, try it in criminal court w/due process and a jury. Children are not entitled to perfect parents because there are none. Any Family forum must defer to the heavy presumption parents act in their child’s best interest while exercising their fiduciary parental authority. Troxel v. Granville]

From this perspective, courts’ persistent focus on mothers’ responsibility for fathers’ relationships with their children smacks of patriarchy, and the beliefs that fathers should not be criticized and that mothers and children must respect their paternal rights regardless of their behavior (DV LEAP et al. Brief, Rathus 2020, Sheehy and Boyd 2020, Elizabeth 2020).

[So long as Family Court acts like a dependency hearing lite, no good can come of it. It’s an adversarial forum. Abolish it. Not only should the child respect the father’s parental authority as well as the mother, but the State is required to do so too except a lawless court respects no one. SCOTUS ruled the state has no legal authority to substitute its judgment for a fit parent’s. If an allegation of child abuse is to be made, try it in criminal court where some protections exist.]

This does not mean to suggest that one parent’s disparagement of the other to a child is unproblematic. [Unproblematic? You’re kidding? You’re trivializing parental alienation.] It does, however, suggest that if a child is frightened or hostile due to a parent’s conduct, regardless of potentially sub-optimal contributions from the preferred parent, the priority should be on curing the original reasons for the child’s fear or hostility, i.e. the parent who has frightened or angered the child should be responsible for addressing it. [Some kids are assholes. Ever raised one? Other’s are heavily influenced by a parent who is an asshole. Stop minimizing the child abuse resulting from PAS.]

Indeed, if enraged or traumatized protective parents – who may behave inappropriately in their fight to keep their child safe – see a court holding the abuser accountable by asking him to remedy the relationship consequences of his abuse, such protective parents are likely to become less enraged and traumatized – and so, less ‘alienating.’ [Conjecture calling for speculation.]

Conclusion

The Family Court Outcomes Study provides the first set of national, objective data describing what U.S. courts are doing when confronted with abuse and alienation claims. The data support the widespread critiques of family court proceedings sending children into the care of destructive and dangerous parents. The gender disparity in how much more powerfully alienation claims work for fathers as opposed to mothers also reinforces critics’ claims that, in abuse cases, alienation is little different from PAS, operating in an illegitimate, gender-biased manner. At the same time, the Study’s evidence that alienation need not be – and is not – gendered in non-abuse cases is a reminder to abuse professionals that alienation may have some independent legitimacy. Hopefully these nuanced findings will encourage specialists on both sides of the ideological divide to turn their 102 J. S. MEIER attention to ensuring that alienation’s use is constrained so as to avoid its misuse in abuse cases while exploring its legitimate contours in non-abuse cases. Notes 1. The author’s former non-profit organization, the Domestic Violence Legal Empowerment and Appeals Project (DV LEAP), receives 30–40 urgent requests for help per month from protective parents – primarily mothers – from across the country; similar reports have been made by other domestic violence organizations and lawyers. 2. This paper uses the term ‘child abuse’ to refer to any sort of child abuse – physical or sexual. When only one is intended, it is specified. 3. This describes the scenario found in well over a thousand custody cases reviewed by the author and described by other attorneys and litigants. 4. A well-regarded custody evaluator suggested to the author that the preferred parent, even if a victim of abuse by the other parent, should be expected to ‘take the high road’ and help repair the child’s relationship with the abusive parent. For a powerful example of this singleminded focus on the preferred parent over an abusive and frightening other parent, see Brief of Amici Curiae DV LEAP et al, available at https://drive.google.com/file/d/ 10dTGOh2AZLVPASBCiC3yFjeQ8LcC4sqw/view (describing case where father had abused mother and was harsh and terrifying to child, yet only mother was blamed for child’s resistance to contact). 5. It is well known that male batterers typically denigrate the mother to the children and aggressively seek to instill children’s disrespect and hostility to her (Meier 2009). However, courts paid little attention to alienating conduct in this context; it only became a behavior of grave concern to courts after it was newly coined as a basis for disbelieving mothers’ abuse claims (Id.). Thus, the mere fact that abusive men may alienate children against their mothers does not lessen abuse specialists’ concerns about the misuse of alienation claims to deny mothers’ abuse claims. 6. The Study team consisted of Joan Meier (Principal Investigator), J.D., Sean Dickson,J.D., MPh; Leora Rosen, PhD; and Chris O’Sullivan, PhD (consultants); with Jeff Hayes, PhD, Institute for Women’s Policy Research (contractor). Particular thanks are owed Sean Dickson, whose inter-disciplinary expertise made him a critical ‘bridge’ and translator for the team. 7. See Meier and Dickson (2017). 8. Allegations were coded as ‘credited’ if the court expressly found them to be true, or a criminal conviction existed. This paper uses ‘credited,’ ‘believed’ and ‘proven’ interchangeably. 9. The categories ‘domestic violence,’ ‘child physical abuse’ and ‘child sexual abuse’ include only cases where that was the sole type of abuse claimed. Where multiple types of abuse were alleged, they are captured in the ‘mixed’ categories (DVCh or CPACSA). When coding whether abuse claims were credited, mixed abuse cases were coded ‘credited’ if one or both of the types of abuse was credited. 10. ‘Alleged’ means the abuse claim may or may not have been credited. 11. This finding is significant at the P < .05 level (CI 1.01–6.36). The difference in rates between CPA and mixed CPA/CSA is not statistically significant. 12. We conservatively only coded cases as alienation cases if the court used that word. When courts used similar analyses but different language, cases were coded as a.k.a. (‘AKA’) cases. AKA cases included in the study were limited to those in which courts expressly found one parent committed such conduct, not those in which it was claimed but not found by the court. Discussion of these findings are beyond the scope of this article. 13. The small number of ‘paradigmatic’ cases (222) – and of cases with explicit alienation claims by either parent (669) in the entire dataset – surprised the Study team. There were also 304 AKA cases. JOURNAL OF SOCIAL WELFARE AND FAMILY LAW 103 14. For simplicity and efficiency, these data are pulled from the Study directly, without Tables or Figures. 15. A litigant was coded as winning if they ‘substantially won,’ i.e. received all or part of their own custody/visitation request or defeated the other parent’s request. 16. The difference is not statistically significant at the .05 level, but it is at the 0.1 level. 17. This author has previously proposed such an approach (Meier 2010). 18. Milchman’s peer-reviewed model (2019) requires all legitimate reasons for a child’s discomfort with a parent to be ruled out before alienation can be considered a causal factor. Disclosure statement No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author. References Baker, A., 2019. About parental alienation syndrome [online]. Available from: https://www.amyjl baker.com/parental-alienation-syndrome.html [Accessed 21 July 2019]. Bala, N., 2018. Powerpoint, parental alienation: social contexts and legal responses. 5th Annual Conference of AFCC, Australia. Bernet, W., et al., 2017. An objective measure of splitting in parental alienation: the parental acceptance-rejection questionnaire. Journal of forensic sciences, 63 (3), 776–783. Bruch, C.S., 2001. Parental alienation syndrome and parental alienation: getting it wrong in child custody cases. Family law quarterly, 35 (3), 527–552. Center for Judicial Excellence. US divorce child murder data [online]. Available from: http:// centerforjudicialexcellence.org/cje-projects-initiatives/child-murder-data [Accessed 30 August 2019]. Children and Family Court Advisory and Support Service (CAFCASS). Typical behaviours exhibited where alienation may be a factor tool. [online]. Available from: https://www.cafcass.gov.uk/ grown-ups/professionals/ciaf/?highlight=CIAF [Accessed 21 July 2019]. Drozd, L.M., Kuehnle, K., and Olesen, N.W., 2011. Rethinking abuse and alienation with gatekeeping in mind [online]. Available from: http://www.lesliedrozd.com/lectures/ AFCCOrlando0611_DrozdKuehnleOlesen.pdf [Accessed 21 November 2019]. Drozd, L.M. and Olesen, N.W., 2004. Is it abuse, alienation, and/or estrangement? A decision tree. Journal of child custody, 1 (3), 65–106. DV LEAP. Legal resources [online]. Available from: https://www.dvleap.org/legal-resource-librarycategories/briefs-court-opinions. [Accessed 30 June 2019a]. DV LEAP. Training resources [online]. Available from: https://www.dvleap.org/legal-resourcelibrary-categories/training-materials [Accessed 30 June 2019b]. DV LEAP et al., 2019. Brief of amici curiae [online]. Available from: https://drive.google.com/file/ d/10dTGOh2AZLVPASBCiC3yFjeQ8LcC4sqw/view [Accessed 20 November 2019]. Elizabeth, V., 2020. The affective burden of separated mothers in PA(S) inflected custody law systems: A New Zealand case study. Journal of social welfare and family law, 42 (1), 118–129. Faller, K.C., 1998. The parental alienation syndrome: what is it and what data support it? Child maltreatment, 3 (2), 100–115. Gardner, R.A., 1992. The parental alienation syndrome: A guide for mental health and legal professionals. Cresskill, NJ: Creative Therapeutics. Gottlieb, L., May 2019. Conversation with author at AFCC 56th annual conference. Toronto, Canada. Johnston, J., 2005. Children of divorce who reject a parent and refuse visitation: recent research and social policy implications for the alienated child. Family law quarterly, 38 (4), 757–775. 104 J. S. MEIER Johnston, J. and Kelly, J., 2004. Rejoinder to gardner’s “Commentary on Kelly and Johnston’s ‘The alienated child: A reformulation of parental alienation syndrome”’. Family court review, 42 (4), 622–628. Kruk, E., 2018. Parental alienation as a form of emotional child abuse: current state of knowledge and future directions for research. Family science review, 22 (4), 141–164. Lapierre, S., et al., 2020. The legitimization and institutionalization of ‘parental alienation’ in the Province of Quebec. Journal of social welfare and family law, 42 (1), 30–44. Meier, J., 2003. Domestic violence, child custody and child protection: understanding judicial resistance and imagining the solutions. American university journal of gender, social policy & the law, 11 (2), 657–731. Meier, J., 2009. A historical perspective on parental alienation syndrome and parental alienation. Journal of child custody, 6 (3–4), 232–257. Meier, J. 2010. Getting Real About Abuse and Alienation: A Critique of Drozd and Olesen’s Decision Tree. Journal of Child Custody, 7 (4), 219–252. Meier, J. and Dickson, S., 2017. Mapping gender: shedding empirical light on family court’s treatment of cases involving abuse and alienation. Law & inequality, 35 (2), 311–334. Milchman, M.S., 2017. Misogynistic cultural argument in parental alienation versus child sexual abuse cases. Journal of child custody, 14 (4), 211–233. Milchman, M.S., 2019. Commentary on “Parental alienation syndrome/parental alienation disorder” (PAS/PAD): a critique of a “Disorder” frequently used to discount allegations of interpersonal violence and abuse in child custody cases. APSAC Advisor. Neilson, L.C., 2018. Parental alienation empirical analysis: child best interests or parental rights? (Fredericton: muriel McQueen Fergusson centre for family violence research and vancouver: the FREDA centre for research on violence against women and children). [online]. Available from: http://www.fredacentre.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/Parental-Alienation-Linda-Neilson. pdf [Accessed 21 November 2019]. Rathus, Z., 2020. A history of the use of the concept of parental alienation in the Australian family law system: contradictions, collisions and their consequences. Journal of social welfare and family law, 42 (1), 5–17. Saini, M., et al., 2016. Empirical studies of alienation. In: L. Drozd, M. Saini, and F. Olesen, eds. Parenting plan evaluations: applied research for family court. 2d ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 374–430. Sheehy, E. and Boyd, S.B., 2020. Penalizing women’s fear: intimate partner violence and parental alienation in Canadian child custody cases. Journal of social welfare and family law, 42 (1), 80–91. Silberg, J., Dallam, S., and Samson, E., 2013. Crisis in family court: lessons from turned-around cases. Final Report to the Office on Violence against Women, Department of Justice. [online]. Available from: http://www.protectiveparents.com/crisis-fam-court-lessons-turned-aroundcases.pdf. [Accessed 21 November 2019]. Thoennes, N. and Tjaden, P.G., 1990. The extent, nature and validity of child sexual abuse allegations in custody/visitation disputes. Child abuse & neglect, 14 (2), 151–163. Thomas, R.M. and Richardson, J.T., 2015. Parental alienation: thirty years on and still junk science. The judges’ journal, 54 (3), 22–24. Trocmé, N. and Bala, N., 2005. False allegations of abuse and neglect when parents separate. Child abuse & neglect, 29 (12), 1333–1345. Warshak, R.A. 2019. When evaluators get it wrong: False positive IDs and parental alienation. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law. [Advance Online publication]. Available from: https://doi. org/10.1037/law0000216 Zaccour, S., 2018. Parental alienation in Quebec custody litigation. Les Cahiers de Droit, 59 (4), 1073–1111. Zorza, J. and Rosen, L., 2005. Guest editors’ introduction. Violence against women, 11 (8), 983–990.